LILONGWE (Malawi), June 22 (BERNAMA-NNN-IRIN) — The malaria vaccine that has eluded medical science for decades is now within reach, with the final phase of clinical trials underway in seven African countries, including Malawi, where the disease claims 6,500 lives a year, most of them children under the age of five.

LILONGWE (Malawi), June 22 (BERNAMA-NNN-IRIN) — The malaria vaccine that has eluded medical science for decades is now within reach, with the final phase of clinical trials underway in seven African countries, including Malawi, where the disease claims 6,500 lives a year, most of them children under the age of five.

Tisungane Mvalo, head of the research team at the Malawian trial site, which is being run in partnership with the University of North Carolina’s Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, said the current methods for controlling the incidence of malaria in Malawi have had limited success.

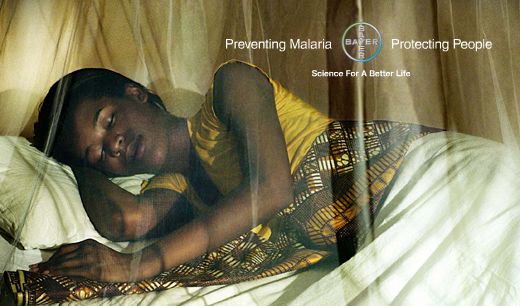

“We have had a moderate reduction in infant mortality from interventions like bed nets and insecticides but malaria remains the leading cause of infant mortality,” he said. “There still needs to be an additional intervention.”

The multi-country trial of the malaria vaccine RTS,S, made by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, is one of the largest ever carried out in sub-Saharan Africa.

With funding from GlaxoSmithKline and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative – an NGO that develops research for malaria – 15,000 newborns and infants are being inoculated at 11 sites across the region.

The children are then monitored over a period of 36 months to assess the effectiveness of RTS,S, which in previous studies reduced cases of severe malaria in infants by 53 percent. If the results, due to be released later this, year confirm the vaccine’s efficacy in preventing malaria, it could be made available as early as 2015.

“It’s a very exciting time,” said PATH Director Dr Christian Loucq, speaking from his office in Washington. “We have estimated in our models that a vaccine like this could save hundreds of thousands of lives a year.”

A malaria vaccine would not only save lives, it would also alleviate the great burden of the disease on health systems in economically stretched developing countries.

Dr Karl Seydel, a paediatrician at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi, said the impact of the disease on the public health system was “overwhelming” – 5.5 million cases of malaria, equivalent to a third of the country’s population, were reported in 2010.

“It drains the resources,” he told IRIN. “We could use that money for other things; we could build more hospitals or hire more nurses.”

He estimated that during the rainy season, when bites from mosquitoes infected with the malaria parasite are most common, about half of all admissions to the hospital’s paediatric ward were due to malaria. The ward was designed for 150 patients but often has to accommodate twice that number.

Malawi has a good track record for immunizing children: 98 percent have received the standard vaccines recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The addition of a malaria vaccine, even at 50 percent effectiveness, could greatly reduce the number of children needing expensive hospital care.

Malaria prevention has been less successful than was hoped. According to the 2010 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey, about 70 percent of households have bed nets, but just half the children under five are using them.

Mvalo said the adults in a household often used the nets, even though children are most susceptible to developing severe malaria. In some parts of the country mosquitoes have also started showing resistance to insecticides.

“Each control method has its shortfalls,” Mvalo said. “That is why a vaccine is a good alternative – not a replacement, but a good alternative.”

Most researchers agree that a malaria vaccine will not substitute for current preventative measures, but could greatly reduce mortality from the disease and create huge financial gains for countries where malaria is endemic. Public health researchers estimate that in such countries, malaria directly absorbs one percent of GDP, excluding indirect costs like loss of work hours.

“Solving the problem of malaria would very much help in terms of economic development,” said Loucq.

— BERNAMA-NNN-IRIN