Maternal death stalks Malawi’s rural poor

Published on June 27, 2011 at 11:30 AM by FACE OF MALAWI

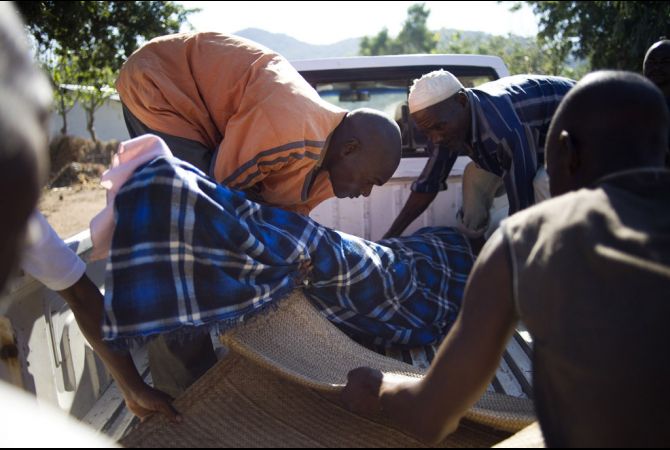

SALIMA, Malawi – She arrived wrapped in a pink blanket, dead.

Family members unload the body of Aliyatu Alola, 24, who died on her way to the Salima District Hospital, Salima, Malawi on June 3, 2011. Photo by: Dominic Chavez

A Toyota pick-up pulled up to the entrance of the maternity ward at Salima District Hospital, carrying Aliyatu Alola, 24 years old and seven months pregnant, in the truck bed.

Two dozen women with fearful eyes, some only hours away from delivering their babies, circled around a nurse who reached for the still-warm hand of Alola. The nurse found no pulse and searched the woman’s face for a clue. She saw pale circles around her closed-shut eyes, a sign of anemia, common in both pregnancy and malaria. The nurse then placed a fetoscope on the woman’s stomach, and heard nothing. The heart of the fetus, too, had stopped.

In the maternity ward, all turned silent.

Malawi has one of the highest maternal death rates in the world, even though it has made great strides in the last decade. For a woman here, there’s a one-in-36 chance of dying in her lifetime during birth or in the late stages of pregnancy, which are 58 times greater odds of death than for a woman in United States.

“Every two weeks something like this happens. Sometimes it’s a little baby, sometimes a pregnant woman. It’s dangerous when health care is so far away.”

~Mndola Village chief Sam Masese

President Barack Obama’s Global Health Initiative (GHI), which started two years ago, decided to make the improvement of maternal health its main focus in Malawi. In doing so, the administration waded head-on into the ideologically charged issue in Washington of family planning — a political firestorm lying in wait because of conservatives’ staunch opposition to any funding for abortions.

For Malawi, where 72 percent of the population of more than 13 million people lives on less than $2 a day, observers say that the U.S. government moved slowly at first as it grappled with bureaucratic issues over how to use money earmarked for AIDS programs and expand it into family planning services. But the issue never blew up here, in part because abortions are illegal in Malawi.

Instead, GHI’s challenge today comes from an entirely different source: an eruption of political battles between the Malawi government and its foreign donors that threatens to disrupt the continuation of even basic services.

The U.S. program — which jumped to $100 million in 2010 from $75 million the year before — is poised to expand on a variety of fronts, including making health care more accessible to pregnant women, training more nurses and community health workers, and expanding family planning out into the country’s most remote communities.

But not all is going according to plan here. Over the last year, the problems have multiplied to include corruption charges against the system of buying drugs and supplies; the enforcement of an anti-gay law; the Global Fund’s rejection of a $565 million plan due to mostly technical reasons; and a recent high-stakes staredown between Malawian President Bingu wa Mutharika and the British government that has led to the suspension of future Department for International Development (DFID) funding totaling $121 million annually.

The Mutharika-British battle escalated after the Malawian leader ordered the expulsion of the British ambassador, Fergus Cochrane-Dyet, over a leaked cable that referred to the president as “autocratic and intolerant of criticism.” DFID then suspended new funding starting in July, citing concerns of corruption, accountability and the government’s spending on “luxury items” such as a $22 million airplane and a fleet of expensive cars.

Some 40 percent of Malawi’s budget comes from foreign donors, and Great Britain is the country’s largest donor, contributing $121 million in 2010-11, or one-fifth of all donor funds, according to government budget figures. (The United States is Malawi’s second largest bilateral donor.) In addition, the World Bank is withholding $40 million in funding pending further reviews and Germany suspended $16.5 million in funding because of Malawi’s anti-gay laws.

Now, according to one senior U.S. health expert, much depends on the Malawi government’s actions in the next few months.

“The ability of our efforts in GHI to sustain and expand health outcomes will be strongly impacted by the will of the Malawian leadership, both within the government, civil society, and private sector,” Mamadi Yilla, GHI planning leader for Malawi, said at an event in late May at the Kaiser Family Foundation in Washington, D.C. “We are hopeful that as we in good faith adjust the way we do business as the US government, that the government of Malawi internally make its own steps to strengthen the areas of our joint response that only they can inform and influence.”

In the meantime, U.S. efforts continue — with hopes that the government-donor relationships are soon repaired.

In Lilongwe, the country’s capital, at the office of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Lilly Banda, USAID’s deputy team leader in the Health Office, said the efforts to reduce maternal mortality were unfolding across many programs. These include antiretroviral treatment for more HIV-positive pregnant women, forming closer relationships with traditional and religious leaders, such as efforts to engage Muslim leaders on family planning, and expanding health services into community health posts.

She said one number highlighted the problem, pointing out the need for family planning: Women in their reproductive years had an average of 5.7 children in 2010, according to a Demographic and Health Survey, down only slightly from an average of 6.3 children in 2004.?? Malawi, Banda said, had made some progress in increasing the use of modern contraceptives, to 42 percent of women in 2010, compared to 28 percent. But she said it wasn’t enough. “Most people using family planning have already had their desired number of children,” Banda said. “The missing link is reaching the teenagers. What needs more focus is youth-friendly health services. Teenage pregnancy is still very, very high in Malawi.”

In Mndola Village, a two-hour drive east from Lilongwe, a U.S.-funded effort to expand family planning was evident in the three-room house belonging to Amon Chimphepo. ??Chimphepo, 35, is a community-based distribution agent. He has a high school education, and he has undergone U.S.-funded training to educate couples about family planning, conduct couples counseling, and to administer HIV rapid tests. Like other community-based workers, the U.S. package also includes a single-gear bicycle, backpack, rain coat, umbrella, solar charger, and a phone. He makes his rounds on his bicycle, carrying materials in his backpack. He sends text messages over the phone to a central collection service that records the numbers of people he has helped.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel: