Theme: From small farmers to big levers: how can smallholders best link up to improve their livelihoods?

‘I have forty followers!’ Jackson Chagoma announces with pride. ‘They often contact me for advice.’ A rangy, middle-aged man with white-hair and a chequered, short-sleeve shirt, Chagoma is not a lay preacher – or a social media acolyte – but one of Malawi’s growing legion of ‘lead farmers’.

‘I have forty followers!’ Jackson Chagoma announces with pride. ‘They often contact me for advice.’ A rangy, middle-aged man with white-hair and a chequered, short-sleeve shirt, Chagoma is not a lay preacher – or a social media acolyte – but one of Malawi’s growing legion of ‘lead farmers’.

As well as tending his smallholding in Mitundu, 25 miles southwest of the capital Lilongwe, Chagoma participates in a scheme to teach farmers in his village about everything from irrigation techniques and composting, to business management and bookkeeping. ‘My followers come to look at my garden, they come to learn,’ he explains.

It’s not difficult to see why Chagoma’s farm is so popular. It’s harvest season and tall, healthy ears of green maize sway gently in the midday breeze. A dairy cow lazes in the shade. Like 97% of Malawi’s farmers, he grows maize. In 2005, this narrow patch of land produced barely 25 50kg bags of grain. This year’s yield will be more than double that, plus groundnut and manioc (cassava). Enough to feed his wife and five children, with surplus left over to sell at market.

Global food security is heavily reliant on smallholders like Jackson Chagoma. About one-third of the world’s population depends on farms of two hectares or less for at least part of its livelihood – a figure that rises to 65% in Africa, and 78% in Malawi.

Yet donor assistance for agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa has declined from 18% of Official Development Assistance in 1980 to just 7% in 2007. Andrew Natsios, former director of USAID, described this disinvestment in farming as ‘perhaps the most devastating mistake made by the northern countries and the international financial institutions in the past 15 years.’

In Malawi, agricultural advisory services were decimated. Lacking funds and human resources, the government was unable to tackle problems such as soil erosion or disseminate new farming techniques. When the rains were erratic, crops failed and famine ensued.

In 2003, a cluster of NGOs, working with the Mzuzu Agriculture Development Division in the remote hills of Rumphi, northern Malawi, began a project to encourage farmers to adopt composting practices. Twenty-five farmers were taught to dig pits and irrigation channels. Each was subsequently given around 50 followers to instruct. The lead farmers received no money but did get pushbikes, stationery and a new sense of purpose.

‘The government wasn’t able to supply farming extension workers so we thought why can’t we pick some of the farmers who have the interest, the knowledge, the drive to train the other farmers?’ recalls Amos Zaindi, director of Malawi Self Help Africa (SHA), which was involved in the Rumphi programme with two other NGOs, Find Your Feet and the Development Fund.

Alongside composting and irrigation techniques, all farmers were schooled in facilitation, business, how to access markets and even HIV/AIDS prevention. The results in Rumphi were striking. According to a draft report for Malawi SHA entitled ‘Knowledge Transfer: the Role of Community Extension in Increasing Food Security’, soil fertility improved and follower farmers’ average annual maize yield increased by almost a quarter. For every £1 invested in the scheme smallholders recouped £11.60. During the same period, farmers not included in the project saw their harvest decline significantly. Women, who provide 70% of agricultural labour in Malawi, were represented, too, as both lead and follower farmers.

Mizeck Chagunda, a former lecturer in the University of Malawi now working at the Scottish Agricultural College, attributes the initiative’s success to the shared trust between farmers. Experts can be treated with suspicion, Dr Chagunda explains, but, ‘when it’s one farmer talking to another there’s a shared understanding and respect. That makes all the difference.’

Malawi’s Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security seems to agree. During the last five years, the ministry has expanded the scheme: currently there are around 10,000 lead farmers, although they are still spread too thinly in a country of 15.2 million.

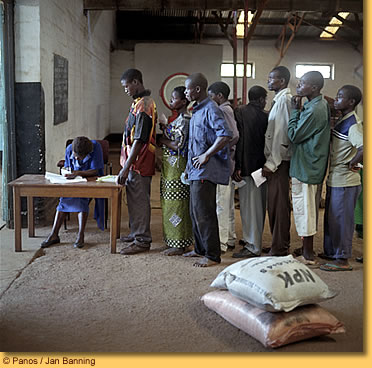

Lead farmers are not Malawi’s only growth area: since 2005, maize production has doubled, real per capita GDP has risen by 40% and the economy has grown by an annual average of 7%. These impressive statistics owe much to the subsidised fertiliser that the government provides to 1.4million of the most impoverished smallholders.

Initially controversial – the subsidy was opposed by IMF and the World Bank – many famers now rely on these 50kg bags of fertiliser, sold at barely 5% of their market price. Isaac Mambo, a lecturer in Malawi’s Bunda College of Agriculture says that while the very poorest cannot afford even the subsidised rate ‘many farmers depend on the support to some extent.’

The subsidy’s future is far from secure. In June, the Department for International Development, which has spent £15 million on the programme over the last four years, announced it was putting its aid commitments to Malawi on hold. The move followed a diplomatic spat with President Bingu wa Mutharika over leaked British embassy cables. Mutharika’s government has said it will only import 90,000 tonnes of fertilizer in 2011, half last year’s figure.

Suspending the subsidy could have serious repercussions, particularly for the 1.1 million people that were food insecure in Malawi last year due to drought, flooding and poor food distribution networks. However, Amos Zaindi believes a readymade, cost-effective, and sustainable alternative is on hand – the lead farmer program.

‘Our climate is changing. The growing season is getting shorter and drier,’ Zaindi remarks. ‘Lead farmer is all about sustainable farming. Using compost or manure helps the soil and means that, even if the rains aren’t good, there’s a 90% chance of a harvest.’

Peter Dorward, an expert on smallholder farming at University of Reading, thinks the lead farmer model has ‘huge potential’ to empower small-scale farmers throughout the developing world. ‘Not only can it lead to effective sharing of information, it stimulates farmers to develop their own ideas,’ Dr Dorward says, adding that smallholders should be encouraged to diversify into other economic areas, instead of relying entirely on agriculture.

Back in Mitundu, Jackson Chagoma recently opened a small grocery shop in his one-storey, brick house. It has proven a big hit with his followers. ‘Many of my farmers come to see my shop. They would like to have their own some day,’ he smiles.

Chagoma is saving money to send his eldest son to secondary school. The hope now is that where one farmer leads, others will follow.