REDD+, forests and food

Published on January 17, 2012 at 8:27 AM by FACE OF MALAWI

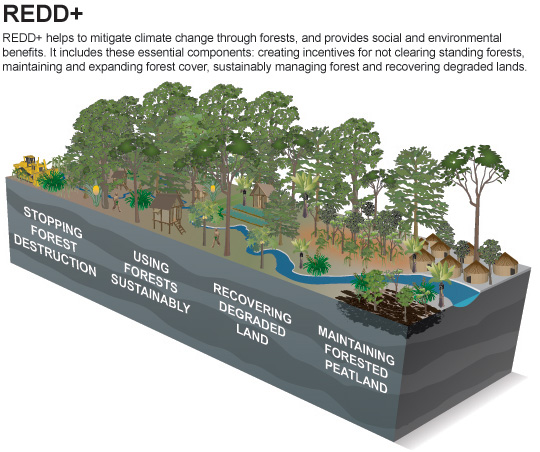

At Durban’s Forest Day 5, the resounding message was that REDD+ will not work if people are hungry. How can we expect the poor to conserve forest resources if their food security – their very survival – rests on the use or consumption of those resources?

At Durban’s Forest Day 5, the resounding message was that REDD+ will not work if people are hungry. How can we expect the poor to conserve forest resources if their food security – their very survival – rests on the use or consumption of those resources?

Part of the problem is a perceived trade-off between cultivating land for agriculture and preserving it as forestland. RECOFTC discusses this, and other opportunity costs of REDD+ for local people, in the latest REDD-Net Bulletin, in which we point out that current market values for forest carbon offsets simply cannot compete with global prices for crops like rubber, oil palm, and coffee.

However, a new study on deforestation and soy production in the Southern Amazon showed that over the past decade, a drop in deforestation has been matched by growth in agricultural output – seemingly a contradiction in terms. Don’t you need to cut down more trees to make room for more agriculture?

What’s happening is agricultural expansion is occurring in areas that have already been deforested or degraded, rather than clearing new land. In fact, between 2006 and 2010, 91 percent of soy expansion occurred in previously cleared cattle pasture. The report notes that part of the change might be due to a massive campaign by Greenpeace pressuring soy producers to refrain from new forest clearing.

This is great news for forests: we can feed the world’s growing population while retaining crucial forest resources. Yet the change in soybean production in the Amazon is on a huge scale; what can small-scale farmers do?

In Malawi, farmers are increasingly integrating forestry and forest resources into their crop rotations to improve productivity and yields in the face of crippling climate change.

Reuters reports that many farmers there are “intercropping trees with maize to provide moisture-preserving shade for the growing corn, while others bury tree leaves in the ground to make the soil more fertile and help retain moisture at planting time.” Farmers are using leaves from fast-growing native trees as fertilizers, either by burying them for six months or by planting trees among crops and letting the leaves that fall to the ground fertilize the soil throughout the growing season. The fertilizer provided by the leaves also helps alleviate the burden of purchasing expensive chemical fertilizers, thereby increasing the farmer’s net income.

Innovative ‘agroforestry’ strategies such as this can help make already cleared agricultural land more productive and allay the opportunity costs associated with protecting forest resources. Not only do programs like this one in Malawi support conserving forest resources (so farmers can turn leaves into fertilizer), but they also help bolster food security and improve rural livelihoods.

It should however be recognized that agroforestry approaches such as this tend to be more labor and financially resource intensive for farmers (at least in the establishment phase) and can be technically challenging. These challenges need to be acknowledged at a policy and donor level, with REDD+ funding potentially used to address these challenges (many private REDD+ projects already use agroforestry as their main approach). If this support is forthcoming, we could see this “win-win” scenario becoming a reality in more and more tropical forested countries.

Written by RECOFTC Assistant Communications Officer Lena Buell