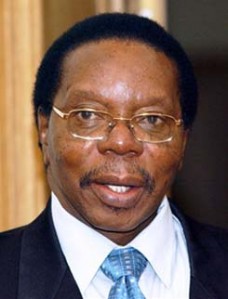

Malawi’s President Bingu wa Mutharika is dead. Mutharika, 78, died of cardiac arrest in Lilongwe hospital on Thursday. Mutharika’s first years in office inspired hope, but in the past year he had turned rogue, and became intolerant of criticism. He cracked down hard on opposition and civil society protests.

He alsto took to running the affairs of both his ruling Democratic People’s Party (DPP) and government like a thug. When he differed with his vice president, Joyce Banda, over the succession in 2010, he had her expelled from the party.

Like many African leaders seeking to create dynasties, Mutharika’s had his brother, Foreign Minister Peter Mutharika, chosen over Ms Banda to be the DPP’s presidential candidate in the 2014 elections. Now that he is dead, you have a Ms Banda who is VP but is not exactly a VP. And junior Mutharika who is the DPP presidential candidate for elections that are two years away, but he is not VP.

Don’t be surprised if the next few weeks in Malawi are turbulent.

Still, Mutharika’s election in May 2009, inspired a column about the meaning of democracy in Africa, that I wrote for the regional publication, The East African:

What are African elections all about? Malawi’s president Bingu wa Mutharika has just won election. The media reported that the election was “viewed as a test for political stability in the poor country.”

Last December’s election (2008) in Ghana was either a “test for the West African region as it struggles for democratic consolidation”, or a “test of Ghana’s democratic credentials.”

Malawi Vice-President Joyce Banda: Was put out to dry by Mutharika.

Malawi Vice-President Joyce Banda: Was put out to dry by Mutharika.

In December 2007, the Kenya election that eventually ended in bloodletting was presented as “a test of Kenya’s young multiparty democracy”, and some international publications said it was “a test of Kenya’s democratic credentials in a continent plagued by election controversies”. Again the word “credentials.”

So, when Uganda held its election in 2006, it was the country’s “first multi-party in 25 years is seen as a test of its democratic credentials”, again “credentials” pops up. There was a more ambitious view on the Uganda case, which stated that the election was a “test of the strength and legitimacy of Uganda’s political institutions.”

When Rwanda last had elections, it was “a test of how far Rwanda has come since the genocide in 1994.”

And in 2005, elections in Tanzania were a “test of the democratic credentials of Tanzania”, and “a test of Tanzania’s hard-earned reputation for stability in a turbulent region.”

However, our politicians themselves rarely frame the elections as a test of policy, national institutions, democratic credentials, or awareness of our countries’ strategic role in their regions. We the media write that stuff because, well, elections in mature democracies are framed that way, or we make these things up to lend an aura gravitas to our elections that they otherwise lack. Foreign minister Peter Mutharika: Pretender to the throne.

Usually, however, elections in Africa are about more basic issues. First, will the incumbent president or his party win the election? If so, will it be an honest victory or will they steal the vote? If they lose, will they do a Robert Mugabe (or Laurent Gbagbo later in Ivory Coast) and openly reject the result and remain in power?

And, if the opposition is beaten fairly because it run a lousy campaign, as it often does, will it do the honourable thing, concede defeat, and congratulate the winner?

For the candidates, usually there are two practical questions question: How much will they need to buy votes? Secondly, how many votes from their tribe can they rely on, and by how many votes will the other tribes vote against him/her?

And for the voters, it is the same two questions, asked differently: First, how much is the candidate willing to pay, either directly, or in sugar or booze for their vote? Second, what is his or her tribe (and sometimes religion? If the candidate is a woman, is she married or single?).

Appreciating this is important, as it helps us not to be too disillusioned with democracy in Africa, because then we understand that it is a work in progress. The vote rigging, buying, and selling are the price we pay for it.

Like all investments, if you put in money long enough and are able to withstand the ill winds, it pays off. Right now, if an African election is fair, it is a bonus we must take and quickly bank. Otherwise, the more important thing is to vote repeatedly until it becomes a good habit.

We lie when we say elections are a “test of democratic credentials”. There is really no democracy or credentials to be tested yet.

No comments! Be the first commenter?