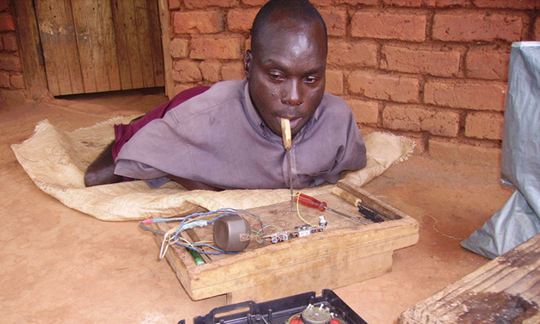

People with hearing impairments in Malawi bemoan the failure to include the use of sign language on state-owned TV. People with visual impairments complain that the bank notes, which Malawi has recently introduced, do not have features to enable them distinguish and identify the different denominations.

And the list goes on. The simple fact is that disabled people are among the most vulnerable, disadvantaged and marginalised people in Malawi – excluded from the enjoyment of their rights despite the Constitution guaranteeing human rights to all people without discrimination.

But – like many other things post-Mutharika – this situation might be about to change as the current government has shown that it is committed to protecting the rights of disabled people.

While the Constitution of Malawi guarantees the right to non-discrimination on the basis of disability under section 20, in reality people with disabilities are discriminated against in many ways – often indirectly.

For example, if the law allows disabled people to be enrolled in schools, but there is no provision of learning materials in Braille or use of sign language for persons with visual and hearing impairments respectively, then there is indirect discrimination on the basis of disability since the disabled will be allowed to attend class but will be excluded from actual learning.

And until very recently, the law relating to people with disabilities was based on the Handicapped Persons Act of 1971, which did not provide for any rights to the disabled. The very out-of-date Act was based on the old-fashioned medical or welfare model of disability, which does not perceive disability as a human rights issue but as a condition of ‘pity’ requiring clinical interventions or charity in order to help the disabled ‘fit into society’.

However, this changed on the 24th May 2012 when parliament finally passed the Disability Bill – almost 8 years after it was drafted! Unlike the previous government, which showed no desire to see the law enacted, Joyce Banda’s government passed the bill into law within two months of assuming power.

The new Disability Act is based on the social model of disability, which perceives disability as a human rights issue and attributes the ‘problems’ associated with disability to the environmental barriers, including individual prejudices and institutional discrimination, which impose restrictions upon the disabled.

The Act provides disability related definitions that mirror the definitions in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) to which Malawi is a state party. The Act defines discrimination as ‘distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability, which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on equal basis, of any human rights or fundamental freedoms, in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or other field’.

The Act guarantees the right to non-discrimination in the fields of health, education and training, social life, culture, sports, recreation, employment, public and political life/affairs, housing, and many others – and seeks to ensure that people with disabilities have access to places and including buildings.

The Act also grants disabled people, who suffer from disability discrimination, remedies enforceable by the courts. Individuals and organisations who practise disability discrimination may be fined or imprisoned and may have their licences revoked.

Furthermore, the Act requires the introduction of a national sign language and establishes a trust fund to pool resources for programmes aimed at ensuring the mainstreaming of disability.

However, the Act could have gone further. It does not provide for the collection of disability statistics and data, or for the establishment of an independent mechanism involving national or other human rights institutions to monitor its implementation – yet these are crucial in the promotion of disability rights.

Lastly, the Act does not make reference to the role of disabled persons’ organisations, persons with disabilities or children with disabilities in its implementation although disability rights advocates emphasise the need for their active participation.

Regardless of its technical strengths and weaknesses, the real test of the Disability Act will be whether or not it has an impact in practice – by helping to promote the rights of people with disabilities.

And the challenge is huge. 98 percent of children with disabilities do not access education. Most places and buildings are not accessible to the disabled, especially wheelchair users. People with mental disabilities are not perceived as disabled people who are entitled to enjoy equal human rights but ‘insane’ or ‘mad’ and are usually institutionalized in mental hospitals.

The new law is certainly an advance on the previous 40-year-old law – and the government should be congratulated for passing it so quickly when there are so many issues to deal with. But to really improve the lot of people with disabilities, the government will have to back up the new law with a clear public commitment to implement its provisions – so that the new policy has a real positive impact in practice.