No featured image set for this post.

African book project starts new chapter

Published on October 1, 2012 at 2:33 PM by FACE OF MALAWI

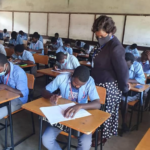

Imagine a first-grade classroom of curious and wiggly students.

Now, picture that classroom with one teacher, 100 to 400 students, and only one textbook per subject per grade. For full effect, envision a dirt floor, no desks and no electricity.

That’s the reality for primary schools in the impoverished Southeast African nation of Malawi — a scenario that the University of Texas at San Antonio has been working to change.

Since 2005, UTSA staff members have overseen two U.S. Agency for International Development grants to supply schools in Malawi and South Africa with 7.7 million books and teachers’ guides. More than one in four adults in Malawi are illiterate, according to UNICEF.

UTSA President Ricardo Romo traveled to Malawi this summer and met with students who had learned to read through the program — including some who had started to write poetry.

“In our familial community of San Antonio, we take care of each other, and we take care of people over there, too,” said Misty Sailors, an associate professor of reading and literacy, who led the effort to reach more than 700,000 children and help train more than 11,000 classroom teachers.

Now, a Boston-based nonprofit leading a new project in Mozambique is planning to provide about 1.2 million books to elementary students there with UTSA’s help, officials said.

Overlapping a four-year project in South Africa, the Read Malawi project got under way in 2009 and ultimately included $8.1 million in grant funding, Sailors said. It’s the largest grant UTSA has received for international research, university officials said.

Romo said the scale of the project says a lot about the faith USAID had in the university and is a boost on the school’s road to “Tier One” research university status.

“These large grants are only given to a select few campuses, and the fact that we could put together a team that could be successful, it’s very prestigious for us,” he said.

Sailors said she was inspired to help Malawi because she had seen a news report on Malawians donating to Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts.

The team is in the process of turning the program over to the Malawi government. It didn’t meet the team’s goal of outfitting every school — the group was initially slated to receive $13 million but that was cut to $8.1 million because of a lack of federal funds, Sailors said. USAID did not respond to requests for comment.

“We resourced over 1,000 educational sites in the country,” Sailors said. “But there are still 4,500 elementary schools in Malawi that don’t have these books. If we would have seen the last $5 million, we could have finished the job.”

The team is trying to drum up funds from private donors, organizations and businesses in Malawi, South Africa and the United States to continue the program, she said.

Sellina Kanyerere-Mkweteza, the program’s former coordinator in Malawi, said it was difficult to see the project stop short of reaching all the schools

“When you see tremendous results and then you can’t reach out to everyone else, it’s really upsetting,” she said. “Every child wants to hold that book that others are enjoying.”

Sailors said the group’s research proves that their approach improved reading achievement and teaching practices.

The university didn’t simply ship over cartons of books. They were printed in Malawi, and the school worked with the Creative Centre for Community Mobilization to set up village reading centers.

The UTSA team worked with the Malawi Institute of Education to develop books that reflect local culture, bringing teachers to workshops and collecting and illustrating oral stories and modern issues.

One tells of a hare and a hyena that learn to cherish their friendship. Another portrays girls moving beyond traditional roles of mother and cook to become a doctor or president of the republic — which is now led by a woman.

“They are pictures and stories they are familiar with,” Kanyerere-Mkweteza said. “The children are more excited in reading the books. … I can tell you, honestly, there are great changes.”

“(Children) are going home and asking questions, like, ‘Why does the zebra have lines on its back?’” she said, adding that some parents have begun brushing up on reading as well.

The books for grades one through three are in both English and the national language, Chichewa. Most of the team works in the UTSA College of Education, but the university’s Institute for Economic Development helped coach Malawian printers in tackling the large-scale book projects.

UTSA doctoral students Lorena Villarreal, 30, and Troy Wilson, 39, who studied the program’s effect this summer, said attendance was up on days the teachers used the books. Students would see and touch the texts.

Wilson described literacy as a bridge to other types of knowledge.

“If you can read, you have the world at your fingertips because whatever book you get your hands on is like traveling to that time and place,” he said.