The other day, I read a newspaper article that made me chuckle. The gist of the article was that some witchdoctors had expressed their wish to seek the permission of the courts to allow them to “take action” against George Thindwa, presumably by bewitching him so he could die or have some misfortune befall him.

For those who may not know, George is a well-known atheist, humanist and sceptic of beliefs in witchcraft. He is currently the executive director of the Association of Secular Humanists (ASH) and works fearlessly to promote the rights of victims of accusations of witchcraft.

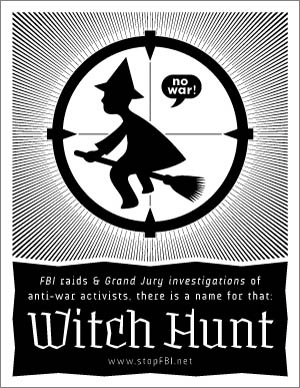

George and ASH have publicly held the position that beliefs in sorcery and the power of witches have no factual basis and that witches do not have the supernatural power that they claim. George has even dared witches in Malawi to prove the potency of their power and offered a sizeable sum of money to any witch who would successfully bewitch him.

When I last checked no witch had collected that sum yet, and George appears to be— to coin a term— un-bewitched. Could it be that the witches were awaiting court clearance to cast their spell on George? Perhaps not. After all, there is no law that requires such clearance and the reference to such clearance appears to be no more than an attempt to avoid admitting that George won the bet.

But it is not really the reference to court clearance that I wish to dwell on despite its comedic potential. It is the more fundamental question of beliefs that underlies the whole saga that I find more engaging. I consider this engaging because it has implications for development.

The law in Malawi allows any person to believe anything as long as that belief does not translate into harm to others. In the words of section 33 of the Constitution: “every person has the right to freedom of conscience, religion, belief and thought, and to academic freedom.” It is therefore one’s right to believe anything.

Thus, for example, if a person chooses to believe that the sun goes round the earth, that is their right under the Constitution. Similarly, if a person chooses to believe that a person can fly in a basket from, say, Jali in Zomba, directly to London to watch the Olympics, it is their constitutional right to do so. It is when such beliefs are translated into actions that harm others that the law intervenes.

Belief is, therefore, essentially a private matter. Nevertheless, in a society that aspires to develop, we should encourage the interrogation of beliefs, including private ones, if they have an impact on the public interest. Thus, for example, we should be having more robust debates on the impact that private beliefs in witchcraft have on development; on how individuals routinely fear to succeed in communities lest they be accused of having got their wealth through witchcraft or be bewitched by jealous folk.

However, I wish to approach the question from a different angle which asks if witchcraft and magic are “real”, as is believed by many Malawians, why do we not mobilize their potency to promote public interest goals, such as national development?

Pick any of the country’s major newspapers and go to the Classified Ads section. Go to the advertisements headed medicine and you will find claims that some, including myself, consider to be wacky, fantastical and outlandish.

Consider the claims of one “doctor”, whose ad appeared in one of the papers last Thursday. Among others, he claimed to have “medicine” which can enable anyone to become wealthy enough to buy 30 buses within 3 days and acquire 20 good houses. Also on offer were charms or medicines that can enable any unemployed person to get a job within one day.

The lovelorn are also covered, with the good doctor promising to enable any woman to get a rich husband within 2 days. Those facing court trials are also assured of “medicines” that fix the trial so that the cases end in their favour.

Let’s ask the obvious question first: who really believes this? Seriously, who believes that there is magical power somewhere which would enable you to move from a position of want to becoming wealthy enough to buy even one bus within a couple of days.

Alternatively, let us, for the sake of argument, assume that all the claims are true. Should we then not simply be marshalling all these doctors, charms and “medicines” for the attainment of national development goals? With such amazing powers in our midst should we really be sidling to donors to beg for donations of government vehicles? Should the good folks at the Ministry of Labour be losing sleep over unemployment rates?

Perhaps we should relinquish the task of development to these amazing men of charms. After all, their timeframes appear to be quite favourable.

On the other hand, perhaps these are just glorified conmen preying on the gullible, as my former college contemporary, George, would argue.

No comments! Be the first commenter?