Poorest countries lead the fight against hunger and undernutrition

Published on April 29, 2013 at 2:59 PM by FACE OF MALAWI

According to new research published by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), low income countries like Malawi and Madagascar and lower middle income Guatemala, are leading the charge against hunger and undernutrition, whilst economic powerhouses such as India and Nigeria are failing some of their most vulnerable citizens.

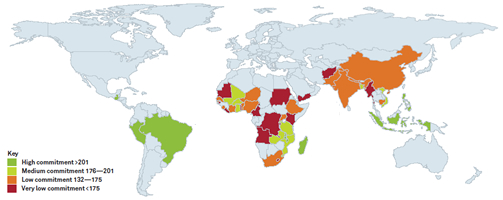

Launched today, the Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index (HANCI) measures political commitment to tackling hunger and undernutrition in 45 developing countries. It is the first global index of its kind showing levels of political commitment to tackle hunger and undernutrition in terms of appropriate policies, legal frameworks and public spending.

One of the key findings from the first round of results from HANCI is that sustained economic growth does not guarantee that governments will make tackling hunger or undernutrition a priority. This may help explain why many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia remain blighted by high levels of hunger and undernutrition.

Globally hunger affects around 870 million people and undernutrition contributes to the deaths of 2.6 million children under five each year. There are many reasons for insufficient progress in reducing hunger and undernutrition. One of these is a “lack of political will” or political prioritisation.

For the first time individuals and organisations in the Global South have a tool that will help to compare government action on hunger and undernutrition with government promises. They can also compare their government with others. In this way, HANCI makes government action more transparent and helps citizens hold their governments to account to ensure that they act to reduce hunger and undernutrition.

“The Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index shines a spot light on what governments are doing, or failing to do, towards addressing hunger and undernutrition,” explained lead HANCI researcher, Dr Dolf te Lintelo. “With millions of lives at stake it is essential that we create greater public accountability on this key development issue. Where high levels of political commitment exist, we could see dramatic decreases in the levels of illness and death caused by chronic hunger and to the irreversible damage to the physical and mental development of children caused by undernutrition. We hope that all those committed to combating hunger and undernutrition, whether in communities, NGOs or governments, will use HANCI as a rallying call for change.”

HANCI uniquely analyses government efforts on hunger and undernutrition, rather than just hunger and undernutrition levels themselves. Hunger and undernutrition are not the same thing and the policies and programmes needed to address them differ. Hunger is the result of an empty stomach whereas undernutrition may result from a lack of nutrients in people’s diets or illness caused by poor sanitation. So governments may support measures to improve sanitation to improve nutrition levels amongst children but this does little to reduce hunger. Likewise, emergency food aid may reduce hunger but it is not aimed at achieving balanced diets.

The new index therefore measures performance on hunger and nutrition separately. It compares 45 countries’ performance on a total of 22 indicators of political commitment to reduce either hunger or undernutrition. These indicators span three areas of government: Policies and programmes designed to tackle undernutrition or hunger; legal frameworks, such as people’s rights to food and social security; and levels of public spending on agriculture and health.

In phase two, HANCI will provide data on the political commitment to tackle undernutrition and hunger in developing countries of donor governments such as the UK and Ireland.

Key findings from HANCI for 2012

Guatemala has claimed the top spot performing best for both hunger and nutrition commitment. Guinea Bissau is the worst performing country.

Whilst much remains to be done and Guatemala continues to have one of the world’s highest child stunting rates (48%), hunger and nutrition outcomes in Guatemala are gradually improving thanks to substantial political commitment and government action. They have improved access to safe drinking water, ensured good levels of sanitation and put in place a Zero Hunger Plan aimed at reducing chronic malnutrition in children under 5 years old. Conversely Guinea Bissau shows the lowest level of political commitment out of all 45 countries with a failure to invest in agriculture or set aside budgets for nutrition services.

Economic growth has not necessarily led to a commitment from governments to tackle hunger and undernutrition.

Despite the fact that many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have achieved substantial and sustained economic growth over the last decade, the prevalence of hunger and undernutrition remains high. To effectively tackle hunger and undernutrition, the poor must benefit from growth and governments need to use additional available resources for public goods and services that will benefit the poor and hungry.

Low wealth or slow economic growth in a country does not necessarily imply low levels of political commitment.

The data shows that in cases where there are serious hunger and nutrition challenges, low aggregate and per capita wealth in a country does not mean that governments are simply unable to act on these. For instance, in Africa, several smaller economic powers (Malawi, Madagascar, The Gambia) are now leading the charge against hunger and undernutrition, leaving traditional African powerhouses (South Africa, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, Angola) in their wake.