Malawi will mark 50 year of independence on Sunday. To celebrate its July 6 golden jubilee, the southeast African country will spend about $370,000 for festivities in the capital city of Lilongwe. The gala at Civo Stadium will include a friendly football (soccer) match between Malawi and Mozambique and live music performances by local artists.

But some people say they are in no mood for rejoicing. A half century on, many Malawians still live in poverty. The country itself continues begging for contributions, with 40 percent of its budget coming from international donors.

Although she could walk to the festivities from her home in Chinsapo Township, a densely populated area of Lilongwe, Stella Mwambakulu said she sees no reason to attend.

“I can’t go there,” the widowed mother of three told the media. “… Why should we celebrate while women are still dying in the hospitals because we can’t access necessary medical care in the hospitals? Women still walk long distances to access potable water. Why should we celebrate when ordinary Malawians still survive on less than a dollar a day?”

Mwambakulu said that instead of spending on a celebration, the government should have budgeted for initiatives to improve the lives of ordinary Malawians.

More than 65 percent of the country’s residents live below the poverty level of less than $2 a day, according to the Center for Social Concern, an organization that conducts monthly cost-of-living surveys.

Its executive director, Joseph Kuppens, said a surge in Malawi’s population – rising from 4 million in 1964 to 15 million today – is one reason for such high poverty levels.

Corruption takes a toll

“Whatever the country is trying to do in order to alleviate and eradicate poverty will be problematic because of the increase in population,” he said.

But Kuppens contends there’s a second factor: “Resources that are supposed to go to the people are actually being used … by the selected few, and that is evident in the whole Cashgate saga.”

The corruption scandal known as Cashgate erupted in 2013, when it was discovered that $30 million in government funds had been siphoned off by civil servants, business people and government officials.

In response, international donors suspended critical funds, citing the need for accountability. There were arrests, promises of tackling corruption and a new election and government installed.

Fahad Assan, Malawi’s former director of public prosecution, estimated the government loses 30 percent of its budget through fraud and corruption annually.

While corruption is cited as a major obstacle to tackling poverty, other structural issues are at play.

Agriculture policy criticized

Ben Kalua, an economics professor at the University of Malawi’s Chancellor College, said the country has experienced economic challenges throughout its history because it lacks thoughtful policies on agriculture, the country’s major source of income. Agriculture accounts for 37 percent of Malawi’s gross domestic product and 85 percent of its export revenue, and employs 80 percent of the labor force.

Most of the agriculture involves small-scale farming.

“You will find that small-holder agriculture takes a big chunk of our budget,” Kalua said, “which has led us into this poverty situation which is still prevalent in Malawi.”

Small farm operations keep the tax base small, he said, leaving the government unable to raise needed funds to improve infrastructure and grow the economy.

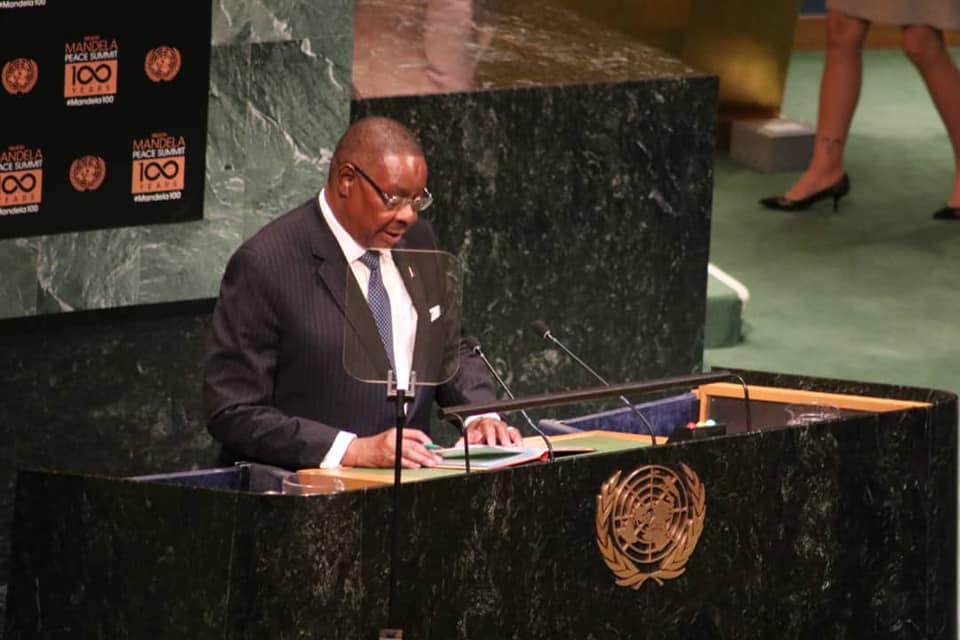

Peter Mutharika, sworn in as president May 31, promised in his first state of the nation address to change Malawi’s status as one of the least-developed countries. He pledged to curb corruption and to reform agriculture, emphasizing irrigation farming and infrastructure development. He also said he would grow the economy by 7 percent in the next five years.

If the president can fulfill those promises, many Malawians say, there will be reason to celebrate when the country turns 55.

No comments! Be the first commenter?