Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, reading levels of students are far below grade level, and Malawi is no exception. Recent results of the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) used by USAID and the Ministry of Education Science and Technology indicate that student reading levels are very weak, with 72.8% of grade 2 students unable to read a basic story, and 41.9% of grade 4 students unable to read a story.

In the South of Malawi in Grade 1, children are being simultaneously taught to read in English and in the local language, Chichewa. While English grammar is relatively straightforward, many English words are hard to spell and read. There are silent letters. There are multiple spellings for the same sound (eg. bear and bare) and different pronunciations for the same word (eg.row the boat, and have a row with someone). This requires children learning to read in English to memorize word lists, learn complex rules and predict unknown spellings. Were they to learn in Chichewa which has letters that always have the same sounds no matter the formation (like most of the world’s languages) they would find reading far easier. It is therefore of grave concern that Malawi is heading towards English-only instruction in schools, and risks leaving those speaking languages such as Chichewa behind.

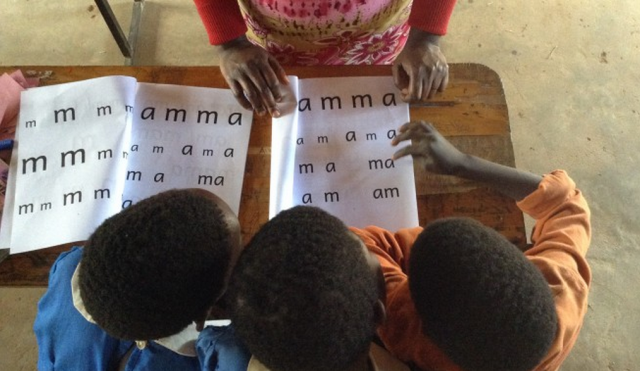

The Millennium Villages Project (MVP), a multi-sectoral initiative led by the Earth Institute, Columbia University has taken on this learning challenge. Community Education Workers use these with children in village learning centres. They show the children a letter, tell them its sound, showing them how that letter can sound different when attached to other letters, and then spend time asking children to practice saying them. The learning approach uses the tried and tested theories of cognitive neuroscience to teach Chichewa. This method teaches students one letter at a time, with letters spaced out and in big font, allowing students to differentiate between different letters and symbols.

According to this method, literacy instruction needs to happen every day, with one new letter introduced per day, focusing on the sound the letter makes, and slowly incorporating other letters to form two, three, and four letter words. The first 1-2 weeks are crucial. If the kids are absent or the teacher does not get them to practice, the unknown letters pile up, and the kids cannot learn them simultaneously or identify them fast enough. By the end of 100 days, students should be able to identify letters and decode, at the very least, with continuous practice to increase speed, fluency and vocabulary. The idea is that these decoding skills will also translate later into English reading, when the identification of letters and the sounds they make can be added onto with the additional phonetic rules in English.

MVP Mwandama is piloting this initiative through its village learning center program. To help guide the instruction, the MVP produced a supplemental textbook with the Primary Education Advisor in the district. We know that many of the poorest children have never seen books, and that initially, for instance, they cannot tell that a small-sized m is the same as larger m. They need specific practice with very large, spaced letters that satisfy the brain’s visual system. If just taught on a blackboard, where letters are often small and bold, the very poor fail at being able to decipher them. This textbook introduces one letter at a time in large font and includes blended sounds, short words, and basic sentences.

The goal behind this innovative program is to see if students improve in their basic reading skills after three months of instruction with this supplemental textbook. Such projects have been previously tested in other contexts such as the Gambia. Conducting it in Malawi, in a non-formal setting, during school vacation with a mix of students from different grades is a unique opportunity to test out this method in a community setting.

Such programmes are cost effective too. With a few thousand dollars the project has reached out to around 1100 children in 27 classes.

Programmes such as these are vital for helping us ensure that students are able to learn, and that they are starting to read from the early grades. They are also crucial for ensuring that ALL students are learning, not just the brightest ones. They show how important it is that, in multilingual societies, children are taught to read by using local languages that are spelled consistently, rather than being forced to learn to read in English. This should be a key point in the targets for education post-2015. It is a point that should also be recognised by Malawi as they forge ahead to start English-only instruction in schools.