Depression Steals Your Soul and Then it Takes Your Friends

Published on July 2, 2019 at 12:05 PM by Face of Malawi

By Patrick

It’s so easy to cut off a friend who is persistently difficult, self-absorbed, nasty, and decidedly “other.” Especially if they cut themselves off first.

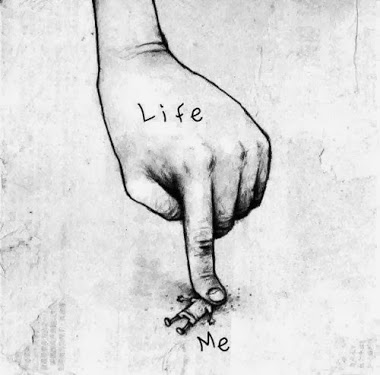

Depression is a thief. It’ll rob you of your time, your thoughts, and your sense of self. But before all of that, it’ll take your friends.

Unlike suicide, depression operates ceaselessly at a low hum. A suicide is a loud clap that ripples through disconnected lives: it is known and felt instantly. But the slip into isolation before suicide, into the murk of the disease, rarely gets so much notice. We like to discuss the black, but not the fade. Subsequently, it’s hard for friends to know how to interact emotionally with depression, and especially as it spans such a longer time period.

For me, the combination of bipolar, borderline personality disorder, and depression has manufactured a consistently brilliant cyanide capsule that I clench between my teeth in any and every relationship. Sadly it’s almost a guarantee that eventually my friendships all get poisoned.

And I understand. For those around me it’s so much easier to cut off a friend who is persistently difficult, self-absorbed, nasty, unpredictable, and decidedly other. And it’s even easier to cut off a friend if they cut themselves off first.

I’ve run this story through my head a million times: one of my best friends—an unnaturally talented writer and a top bloke—slowly began to recede into himself. He cleared all his friends from Facebook, he stopped replying to calls and texts, and then he hauled himself up in his room like a hermit. We all knew what was happening. Friends kept messaging me: “Have you seen X? Is X okay? We should go and see X.”

None of us ever went and saw X. That was two years ago and none of us have seen or talked to him since. He is not dead but he is gone. Hauled up in the mountain cabin of his mind. Losing a friend like this was like seeing a ghost pass through the two walls of a hallway—a kind of vanishing that leaves you feeling uncertain.

Last year I slid back into my own depressive slump, and began copying all the same behaviour. Basically just self-isolating and burning bridges so that within six months I’d lost more friends than someone who proudly boasts about voting for Jil Stein.

A depressive hibernation is not so much a purposeful exile, as a slow-paced locking of doors. When your mind feels groggy and your day is a looping cycle of inaction and despairing thoughts, it can be hard to work up the strength to go to a friend’s gig, grab a coffee, or reply to a text. In my own experience, the disease does so much to convince you of your awfulness, that you start viewing your absence from friends and events as a deformed favour.

You mute yourself for fear that your internal wailing will wreck the vibe for others.

Then this fear of wrecking the fun for others lays on a thick coating of guilt. Depressives—the mad in general—carry a lot of guilt. You wear a person down. Depression is a maelstrom with a sticky gravitational pull. Loved ones who are all buoyancy, care, empathy, and concern, are steadily worn down and thinned-out like seaside pebbles. It is impossibly difficult to pour so much love and worry into a person incapable of reciprocating, and we know this.

So many times I have felt my tongue grow fat and unsteady with attempts to plop out a proper thanks.

That thanks can be uncomfortable and embarrassing for a myriad of reasons. It is hard to tell your girlfriend that just by being there and watching cartoons with you they are keeping you alive, because that puts a certain weight on an otherwise innocuous afternoon. That also puts a burden on a person who doesn’t have—and shouldn’t have—the ability to carry you and cure the incurable.

In that disbelief, the disease toxifies. I’ve told friends their company nauseates me, and told parents they’ve malformed my brain, and told the person I’ve loved that they’ve allowed me to rob a fraction of their life and that’s somehow made them guilty.

If there’s one truth to depression it is that it is both wholly universal and fundamentally solipsistic. It refracts identity like a dark crystal, and what we are taught is a neurochemical experience felt by many, feels doggedly and unique and of your own. You can feel this so intensely that you can convince those closest to you that it’s the case. Then suddenly all parties understand you as a lost cause.

Mental health campaigners consistently put forth the narrative of reaching out—for help and to help. Even though I agree that this is the best method, most people are not equipped to do this, and the guilt that springs up in the rift of that shortcoming is in itself highly destructive.

I felt this acutely when I was unable to help my friend and I feel it now when I am unable to ask for help myself.

The disquieting reality is that depression alone cannot make a person disappear. Friends play a part in the disappearance. And that uncomfortable truth is the reason we do not have this conversation. Also because empathy is finite.

I think that in accepting that neither sufferer nor witness are culpable we can all find some semblance of peace. In that hard admission we can see depression as the interloping thief that it is, and stay the flow of the mad and suffering from our lives.