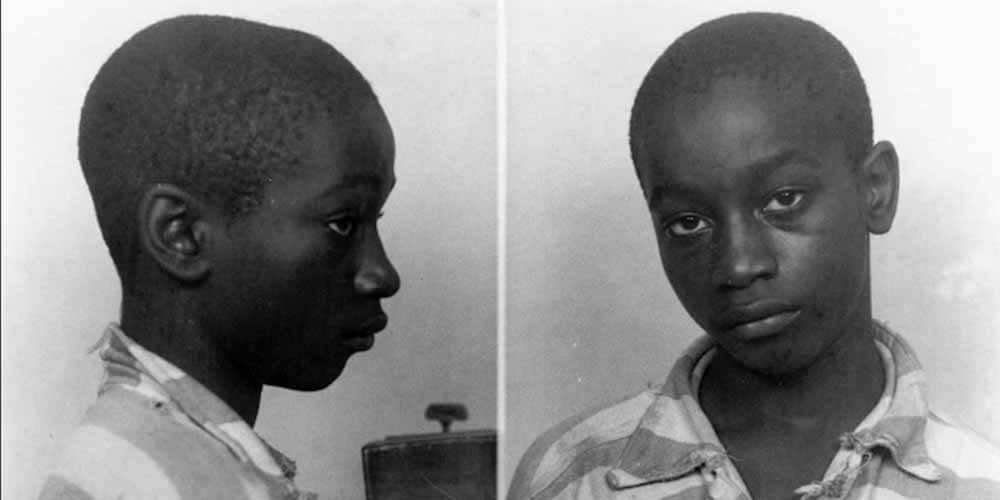

In March 1944, deep in the Jim Crow South, police came for 14-year-old George Stinney Jr.

His parents weren’t at home, His little sister was hiding in the family’s chicken coop behind the house in Alcolu, a segregated mill town in South Carolina, while officers handcuffed George and his older brother, Johnnie, and took them away.

Two young white girls had been found brutally murdered, beaten over the head with a railroad spike and dumped in a water-logged ditch.

He and his little sister, who were black, were said to be last ones to see them alive. Authorities later released the older Stinney – and directed their attention toward George.

“[The police] were looking for someone to blame it on, so they used my brother as a scapegoat,” his sister Amie Ruffner told WLTX-TV earlier this year.

On June 16, 1944, he was executed, becoming the youngest person in modern times to be put to death. On Wednesday, 70 years later, he was exonerated.

He was questioned in a small room, alone – without his parents, without an attorney. (Gideon v. Wainwright, the landmark Supreme Court case guaranteeing the right to counsel, wouldn’t be decided until 1963.)

Police claimed the boy confessed to killing Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, admitting he wanted to have sex with Betty. They rushed him to trial.

After a two-hour trial and a 10-minute jury deliberation, Stinney was convicted of murder on April 24 and sentenced to die by electrocution, according to a book by Mark R. Jones. At the time, 14 was the age of criminal responsibility. His lawyer, a local political figure, chose not to appeal.

Stinney’s initial trial, the evidence – or lack of it – and the speed with which he was convicted seemed to illustrate how a young black boy was railroaded by an all-white justice system. During the one-day trial, the defense called few or no witnesses. There was no written record of a confession. Today, most people who could testify are dead and most evidence is long gone.

New facts in the case prompted Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen to vacate his conviction on Wednesday – 70 years after Stinney’s execution.

Source: omgvoice

“I can think of no greater injustice than the violation of one’s Constitutional rights which has been proven to me in this case,” Mullen wrote.

The case has haunted the town since it happened, but garnered new attention when historian George Frierson, a local school board member raised in Stinney’s hometown, started studying it some years ago. Since then, Stinney’s former cellmate issued a statement saying the boy denied the charges.

“I didn’t, didn’t do it,’ ” Wilford Hunter said Stinney told him. “He said, ‘Why would they kill me for something I didn’t do?’ ”

In 2009, an attorney planned to file statements from Stinney’s family members, but waited because he heard a man in Tennessee, who was not related to Stinney, could offer an alibi for the youth. The man never came forward. It reportedly delayed the new trial, but didn’t stop it.

“South Carolina still recognizes George Stinney as a murderer,” defense attorney Matt Burgess told CNN earlier this year. “We felt that something needed to be done about that.”

New details started to emerge. Stinney’s family claimed his confession was coerced, and that he had an alibi that was never heard. That alibi was his sister, now Amie Ruffner, 77. She said she was with him at the alleged time of the crime, watching their family’s cow graze near some railroad tracks by their house when the two girls rode over on their bicycles.

“They said, ‘Could you tell us where we could find some maypops?’ ” Ruffner remembered them saying, according to WLTX-TV. “We said, ‘No,’ and they went on about their business.”

Stinney was accused of murdering the girls while they picked wildflowers.

Stinney’s family fled their home. His brother, Charles, who is now in his 80s, said in a statement they never came forward because they were terrified.

“George’s conviction and execution was something my family believed could happen to any of us in the family. Therefore, we made a decision for the safety of the family to leave it be,” Charles Stinney wrote in his sworn statement.

Earlier this year, the case picked up speed. At a hearing in January, Stinney’s family demanded a new trial. Mullen heard testimony from Stinney’s brothers and sisters, a witness from the search party that discovered the bodies and experts who challenged Stinney’s confession.

A child forensic psychiatrist testified this week that Stinney’s confession should have never been trusted.

“It is my professional opinion, to a reasonable degree of medical certainty, that the confession given by George Stinney Jr. on or about March 24, 1944, is best characterized as a coerced, compliant, false confession,” Amanda Sales told the court, according to NBC News. “It is not reliable.”

Still, some argued Stinney’s admission of guilt was clear.

At the time a law enforcement officer named H.S. Newman wrote in a handwritten statement:

“I arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney. He then made a confession and told me where to find a piece of iron about 15 inches long. He said he put it in a ditch about six feet from the bicycle.”

Few other documents from that time exist.

James Gamble, whose father was the sheriff at the time, told the Herald in 2003 he was in the back seat with Stinney when his father drove the boy to prison.

“There wasn’t ever any doubt about him being guilty,” he said. “He was real talkative about it. He said, ‘I’m real sorry. I didn’t want to kill them girls.’ “

Indeed, just 84 days after the girls’ deaths, Stinney was sent to the electric chair. Today, an appeal from a death sentence is all but automatic, and years, even decades, pass before an execution, which provides at least some time for new evidence to emerge.

Stinney was barely 5 feet tall and not yet 100 pounds. The electric chair’s straps were too big for his frail body.

Newspapers at the time reported he had to sit on books to reach the headpiece. And when the switch was flipped, the convulsions knocked down the large mask, exposing his tearful face to the crowd.

Frierson and Stinney’s family maintained that they never wanted a pardon.

“There’s a difference: A pardon is forgiving someone for something they did,” Norma Robinson, George Stinney’s niece, told the Manning Times. “That wasn’t an option for my mother, my aunt or my uncle. We weren’t asking forgiveness.”

Instead, they sought what’s called a “writ of coram nobis.” It means, in essence, mistakes were made. (H/T WashingtonPost)