Covid vaccine: How will we keep it cold enough?

Published on December 2, 2020 at 2:31 PM by FACE OF MALAWI

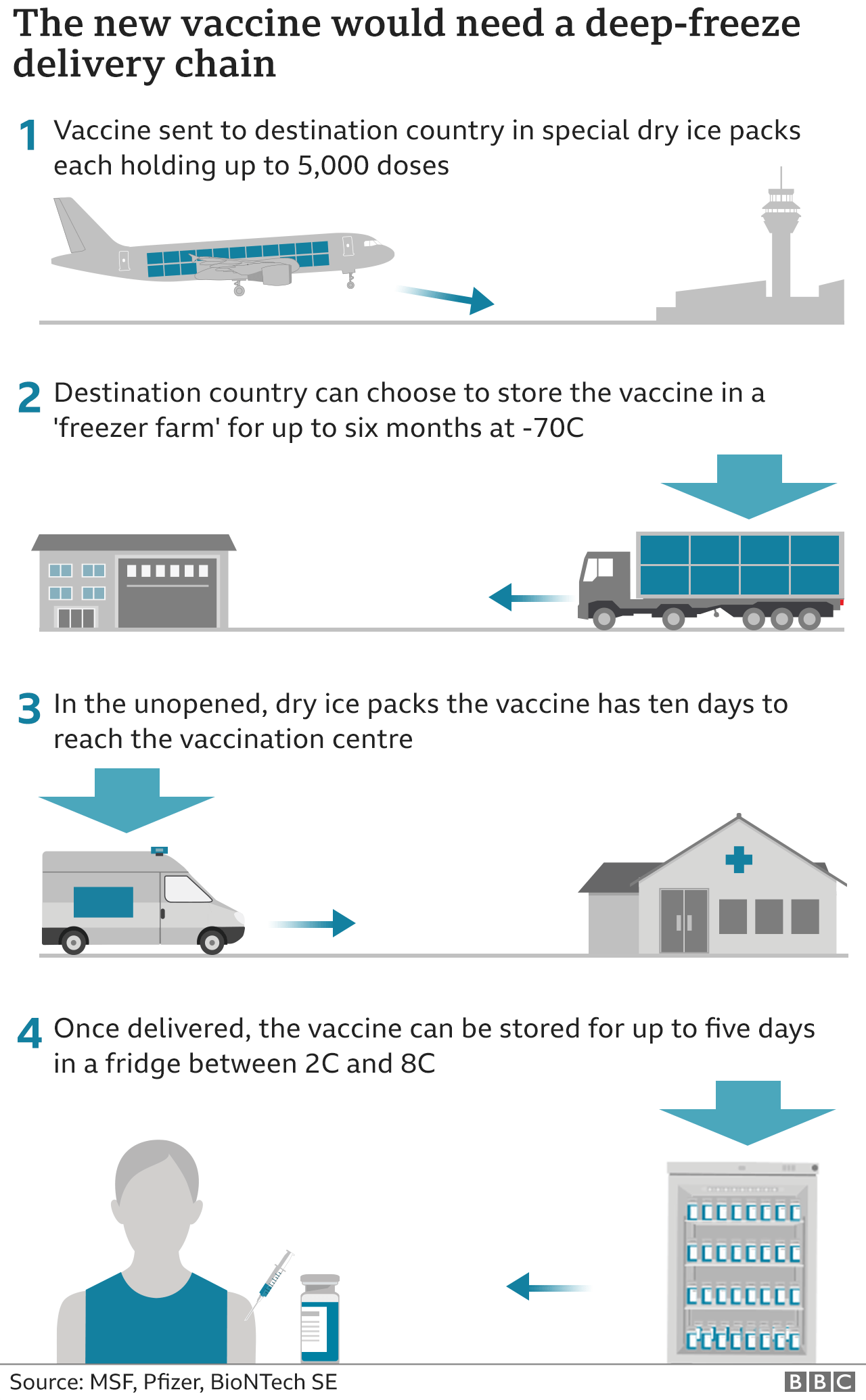

the vaccine needs to be kept at a temperature of about -70C.

Most other vaccines do not need this, so how will this be made to work?

How will it travel?

In the short-term, Pfizer has a plan.

The vaccine will be distributed from its own centres in the US, Germany and Belgium.

It will need to travel both on land and by air and possibly be stored in distribution centres, before being delivered to anywhere the vaccine will be given.

Pfizer has developed a special transport box the size of a suitcase, packed with dry ice and installed with GPS trackers. Each reusable box can keep up to 5,000 doses of the vaccine at the right temperature for 10 days, if it remains unopened.

Wiltshire-based firm Polar Thermals makes similar boxes for other vaccines and counts Pfizer among its clients, but not yet for this particular purpose.

The box is not likely to be cheap. Head of sales Paul Harrison says a standard chilled transport box, which will retain a temperature of up to -8C for five days and is big enough to hold 1,200 vaccines, costs about £5,000 per unit – although they can be reused thousands of times.

His firm uses aerogel as insulation, rather than dry ice – which could be handy if a global carbon dioxide shortage from earlier this year continues to affect the availability of related products, such as dry ice.

The US Compressed Gas Association, however, has said it is committed to meeting demand.

What happens after 10 days?

The vaccine can survive for a further five days once thawed, Pfizer has said, but this does not buy a great deal of extra time.

In the longer-term, Public Health England says that in the UK “national preparations” are under way regarding both central storage and distribution of the vaccine across the country, but has not given details.

As it stands, extreme cold storage is certainly not commonplace, and your local GP is unlikely to have it.

Some institutions, such as universities and research labs, do have the right storage capacity.

In the UK, universities shared resources at the height of the first wave of the pandemic, including PPE-making equipment and ventilators.

The situation in developing countries is even more tenuous.

Burkina Faso, in central Africa, reported last month that it was already short of about 1,000 clinical fridges.

The World Health Organization, in conjunction with UN children’s agency Unicef, has an ongoing project mapping cold storage facilities in anticipation of a Covid-19 vaccine.

Unicef wants to have 65,000 solar-powered cold fridges installed in low-income countries by the end of 2021.