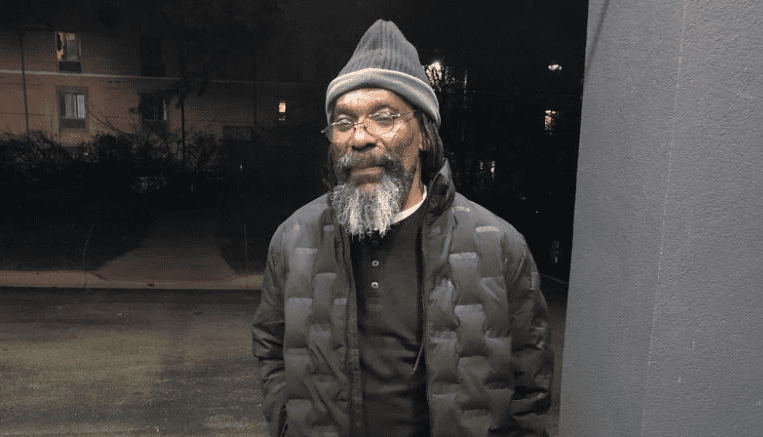

Imprisoned nearly 40 years, Man freed after witness recants her story

Published on December 17, 2020 at 8:30 AM by Face of Malawi

A Michigan man, Walter Forbes, was a young college student in 1982 when he stepped between two groups fighting outside a bar in his small town.

One of the men, Dennis Hall, retaliated the next day, shooting Forbes four times.

Soon afterward, Hall died in an apparent arson fire, and Forbes was sentenced to life in prison without parole, according to court documents.

Now, after serving almost four decades in prison, Forbes has walked free after a key witness recanted her testimony.

A witness comes forward

While on bail for the shooting, Hall died in a fire at his apartment in Jackson. His fiancee was able to escape with their young daughter.

Fire investigators found a blue gasoline container at the scene and evidence of accelerants inside the building’s first floor, according to court documents.

Forbes said he learned of Hall’s death while listening to a morning radio program.

“Some way they’re going to try to frame this on me,” Forbes told CNN. “That thought went through my mind.” Three months after the fire, a young mother came forward.

Annice Kennebrew said she had seen Forbes and two other men carrying red gasoline canisters near the building during the time of the fire and saw them pour gasoline around it, according to court documents.

Kennebrew’s account differed from what fire investigators found. While she described gasoline being poured on the exterior of the building, investigators found charring and evidence of accelerants only on the inside.

One container that smelled of gasoline was found at the scene. It was blue, not red, according to court documents.

One of the accused men passed a polygraph test, and the charges against him were dismissed. A second was acquitted. Only Forbes was convicted.

Twin fires

The jury heard only part of another set of evidence, about another person who stood to gain from the fire. An anonymous tipster called police four days after the fire, pinning the responsibility on the building’s owner.

The tip was deemed inadmissible at the time, according to Forbes’ current lawyer, Imran Syed.

David Jones, who had owned the building for eight years, got it insured two months before the fire, according to fire investigator notes summarized by the defense.

Jones died some time before the Michigan Innocence Clinic took up Forbes’ case, according to Syed.

At trial, Jones testified that the property’s maximum resale value was $35,000. Insurance paid out $50,200, according to court documents.

After Forbes was convicted, a witness came forward, informing the local fire investigator that an acquaintance had admitted setting the fire for Jones in exchange for $1,000, according to court documents.

It was unclear whether authorities followed up on the information. In 1990, Jones pleaded no contest in an arson insurance fraud scheme in nearby Livingston County.

During the investigation, one conspirator mentioned Jones was involved in a 1982 fire in Jackson, according to court documents.

While in prison, Forbes said he was thumbing through a newspaper when he saw an article about the case. He said he felt relieved when he saw how similar the arson cases were.

“It was a pattern with this guy,” Forbes told CNN.

A witness recants

Forbes reached out to the Michigan Innocence Clinic, which started looking into his case in 2010.

The clinic, run by lawyers and students at the University of Michigan, was struck by the use of a single witness to convict a man for murder.

“We knew there were two things we wanted: to speak to the witness and see what her story was. We also knew there had been an alternate suspect from the beginning in this case,” Syed said.

Syed and his team began reaching out to Kennebrew, trying to understand what exactly she had seen. Finally, sick with a respiratory illness, she invited them to a friend’s house in Jackson in 2017.

“She came clean,” Syed said. “She said that at the time of the fire she was 19, and there were two men in the community that took advantage of that.”

Weeks after the fire, two local men approached her and pressured her to implicate Forbes and two other men in the arson.

“They threatened to kill my children, parents, siblings, and me if I did not report to the police and testify at trial that I saw Walter and the other two men set the fire,” Kennebrew said in a sworn 2017 affidavit.

‘I was a kid’

“Everything I told police, and everything I testified to at trial relating to my witnessing the setting of the fire, was a fabrication,” the affidavit continued. “As far as I know, Walter had nothing to do with this crime.”

Kennebrew was hesitant to speak about her testimony when reached by CNN. When asked whether she was pressured before her initial testimony, she said, “It was hard. I was a kid.”

She said she recanted “because it was the right thing to do.”

Kennebrew, Forbes and Syed said it was unclear why the two men pressured her to accuse the trio. Forbes said they may have been feuding with his brother, but he was unsure of the exact reason.

The Jackson County Circuit Court judge heard the case remotely in May and June. The clinic argued Forbes was owed a new trial based on Kennebrew’s recantation and Jones’ 1990 conviction.

“Nothing’s impossible, but if you got no proof, you can’t sustain a conviction,” Syed said.

After reinvestigating the case, the Jackson County prosecutor’s office chose to oppose the Michigan Innocence Clinic’s motion for relief from judgment.

Sad that it took 38 years

In its reply to the clinic’s brief, the county prosecutor argued that Forbes had to “show ‘more probable than not’ that the jury would acquit” were he to be given a new trial.

The prosecutor’s filing also argued that inconsistencies in Kennebrew’s original testimony were insignificant, and she could have “easily” been confused about colors while the rest of her account was sound.

Prosecutors also questioned why the two men would have pressured Kennebrew to testify in the first place. Both men have since died, according to court documents.

The Jackson County prosecuting attorney did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment. The judge threw out Forbes’ conviction this fall, and the county prosecutor filed a motion to dismiss the case.

Forbes walked free November 20. He said he hopes to continue the work he began in prison with prison reform groups. Being released, he said, has been like seeing a “vision unfold.”

Syed became aware of Forbes’ case when he was a law student at the University of Michigan, working at the clinic, and has worked on the case throughout his first decade as a lawyer.

“It’s not that complicated. It’s not a DNA case. It’s not a forensic science case. It’s pretty straightforward,” Syed said. “It’s pretty sad that it took 38 years.”