America’s “longest juvenile lifer” recently walked out of prison a free man. Joe Ligon spoke to BBC World Service about spending nearly seven decades in jail, why he waited so long for freedom, and how he intends to spend the rest of his days.

“I’ve never been alone, but I am a loner. I prefer to be alone as much as I possibly can. Being in prison, I’ve been in a single cell all this time, from the time of my arrest all the way up until my release.

“That helps people like me, who want to be alone – I was the type of person, once I went in the cell and closed the door, whatever was going on, I didn’t see or hear nothing. When we were allowed to have the radio and TV – that was my company.”

It’s perhaps fair to say that prison life rather suited Joe Ligon, to a degree. It allowed him to keep his head down, his mouth shut and out of trouble – all lessons, he says, he has learned in his 68 years behind bars.

And when it came time to retire to his cell at the end of the day, it didn’t bother him there was no-one else there. In fact, keeping his own company was something of a considered choice.

“I had no friends inside. I had no friends outside. But most people that I associated with… I treated them as though they were a friend. And we were cool, we were alright with each other,” he says.

“But I didn’t use that word friend, I learned that that choice of word means a whole lot to a person like me. And a lot of people say that [if you’re a] friend… you can be making a big mistake.”

Ligon has, by his own admission, always been the solitary sort. Growing up in the country with his maternal grandparents in Birmingham, Alabama, he didn’t have many friends and instead remembers fond times with his family, such as the Sundays they spent together watching his other grandfather preach in a local church.

He was 13 when he moved from the deep south to Philadelphia to live in a blue-collar neighbourhood with his nurse mum, mechanic dad and younger brother and sister. He struggled in school and could neither read nor write. He didn’t play sports and as for friends, they weren’t much of a feature.

“I didn’t do too much hanging out. I was the type of person that had one or two friends, that was it for me – I didn’t go for crowds.”

When Ligon “got into trouble” on a Friday evening in 1953, he didn’t really know the people he was with then either. He had met up with a couple of people he knew casually and as they walked around the neighbourhood, they bumped into some other people who were drinking.

“We started asking people for some money so we could get some more wine and one thing led to another…”

He trails off. But he admits the night ended in a stabbing spree in which he was involved, violence which left two people dead and six injured.

Ligon was the first to be arrested. At the police station, he says he quite truthfully couldn’t tell officers who he had been with that night.

“Even the two I did know, I didn’t know their names, I knew them by their nicknames.”

Ligon says he was taken to a police station far from his home in Rodman Street and held for five days, without access to legal help. He says he was angry for a long time that his parents were turned away when they tried to visit.

That week, the then 15-year-old was charged with murder – an accusation he has always denied although he has since accepted in an interview with US broadcaster CBS that he stabbed someone who survived and has expressed remorse.

“They [the police] started giving us statements to sign, that implicated me in murder. I didn’t murder anybody.”

Pennsylvania is one of six US states where life imprisonment carries no possibility of a parole. Ligon faced what was called a degree of guilt hearing, where he admitted to the facts of the case, and the judge found him guilty on two counts of first degree murder.

The teenager wasn’t in court to hear he had been given mandatory life without parole – not unusual given the sentence was a foregone conclusion at the time. But it meant he went to jail without knowing the full terms of his sentence – and it didn’t occur to him to ask anyone.

“I didn’t even know what to ask. I know it’s hard to believe but it was the truth,” says Ligon. “I knew I had to do time, but I had no idea I’d be in prison for the rest of my life. I had never even heard the words ‘life with parole’.

“I’ll tell you how messed up I was as a child – I couldn’t read or write, couldn’t even spell my name. I knew my name was Joe, because that’s what I was referred to as far back as I could remember.”

Ligon says he entered the prison system confused, rather than scared. The main thing on his mind was being away from his family.

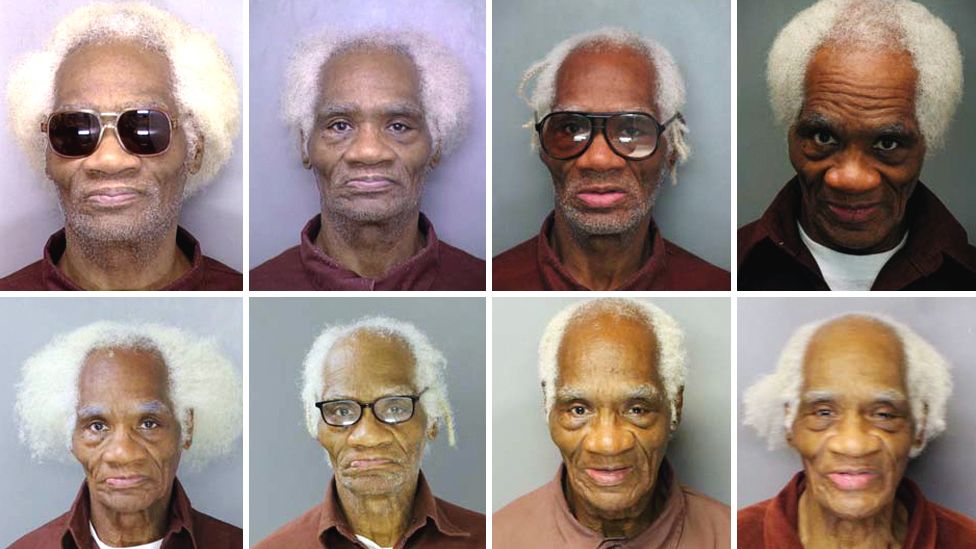

As prisoner AE 4126, Ligon seemingly never questioned how much time he had left to serve. He lived in six jails over 68 years, adapting each time to the routine of prison life.

“They wake you up at 6 o’clock by the bullhorn, by the voice, ‘stand up for count, everybody, it’s count time’… 7 o’clock is meal time, 8 o’clock is work time.”

Ligon sometimes worked in the kitchen and laundry room, but was for the most part a cleaner. After a midday meal, he reported back to his duties. A roll call again in the evening and dinner marked the remainder of his day – prison life remaining largely the same while the world outside changed irrevocably over the decades.

“I didn’t mess with drugs, I didn’t drink in jail, I did none of that crazy stuff that causes people to get killed, I didn’t try to escape, I didn’t give nobody a hard time,” he recalls.

“I stayed as humble as I possibly could – what prison has taught me along with many other things is mind your business, always try to do what’s right, stay away from trouble when it’s humanly possible to do.”

Some 53 years into his sentence, Ligon was told a lawyer wanted to see him.

Buoyed by the US Supreme Court’s ruling in 2005 that juveniles couldn’t be executed, Bradley S Bridge had started looking into what he believed would be the next big legal issue to come out of it – juveniles who had been given life without parole.

At the time, Pennsylvania had 525 prisoners in such circumstances which was the highest in the US, according to Bridge. Philadelphia had 325 – and Ligon was its longest serving. The assistant defender arranged to meet him.

“He was not really aware of his sentence,” says Bridge, from the Defender Association of Philadelphia. “He knew nothing about it until I met with him. It’s kind of interesting he had never given up hope – he was completely optimistic, from the very beginning, always expected that something would be done.”

For Ligon, the meeting was eye-opening. When Bridge showed him a copy of the appeal challenging the legal status of his sentence, it was the first time Ligon learned the terms of his incarceration.

“I realised that I was being mistreated from the time of my arrest. And I was taught and I learned that it was unconstitutional to be sentenced [as a juvenile] without the possibility of parole.”

In 2016, the US Supreme Court ruled all juvenile lifers had to be resentenced. The following year, Ligon was resentenced to 35 years, meaning he could apply for parole due to time served. Bridge urged him to but was met with flat refusal. Ligon felt his sentence had always been unconstitutional, so why should he accept parole, which would mean his liberty was monitored.

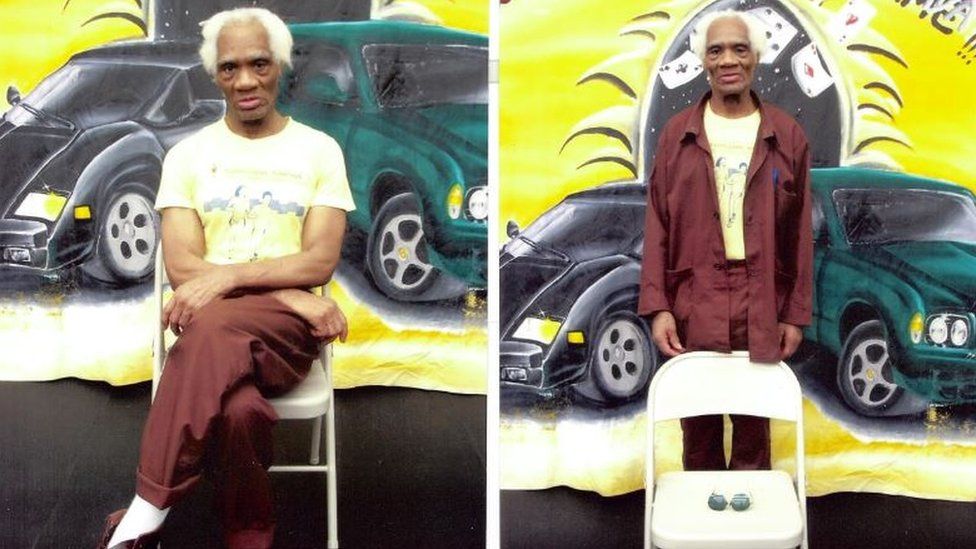

Bridge therefore had to challenge the 2017 judgement and eventually took the case to federal court, where in November 2020, the judge ruled in his favour. When Bridge went to Montgomery County to pick Ligon up on 11 February, he found the former inmate remarkably calm.

“I would have expected a stronger ‘oh my god’ reaction. But he didn’t have that. No drama, nothing.”

Ligon was perhaps simply doing what he had done for decades: keeping his thoughts to himself.

A month since his release, he reflects on the day he left State Correctional Institution Phoenix with a degree of wonder.

“It was like being born all over again. Because everything was new to me – just about everything [changed].” Cars and tall buildings especially, he notes.

The last 68 years have come at a cost to Ligon. He knows he has lost further time by waiting for release without parole – time he could have spent with his family, many of whom have since died.

And yet, as this 83-year-old adjusts to what he has waited so long for, he has few plans. Rather, he’s going to stick to what he knows best.

“I’m gonna do the same thing I’ve been doing my whole life. Give me a job of cleaning, as a janitor.”

BBC World