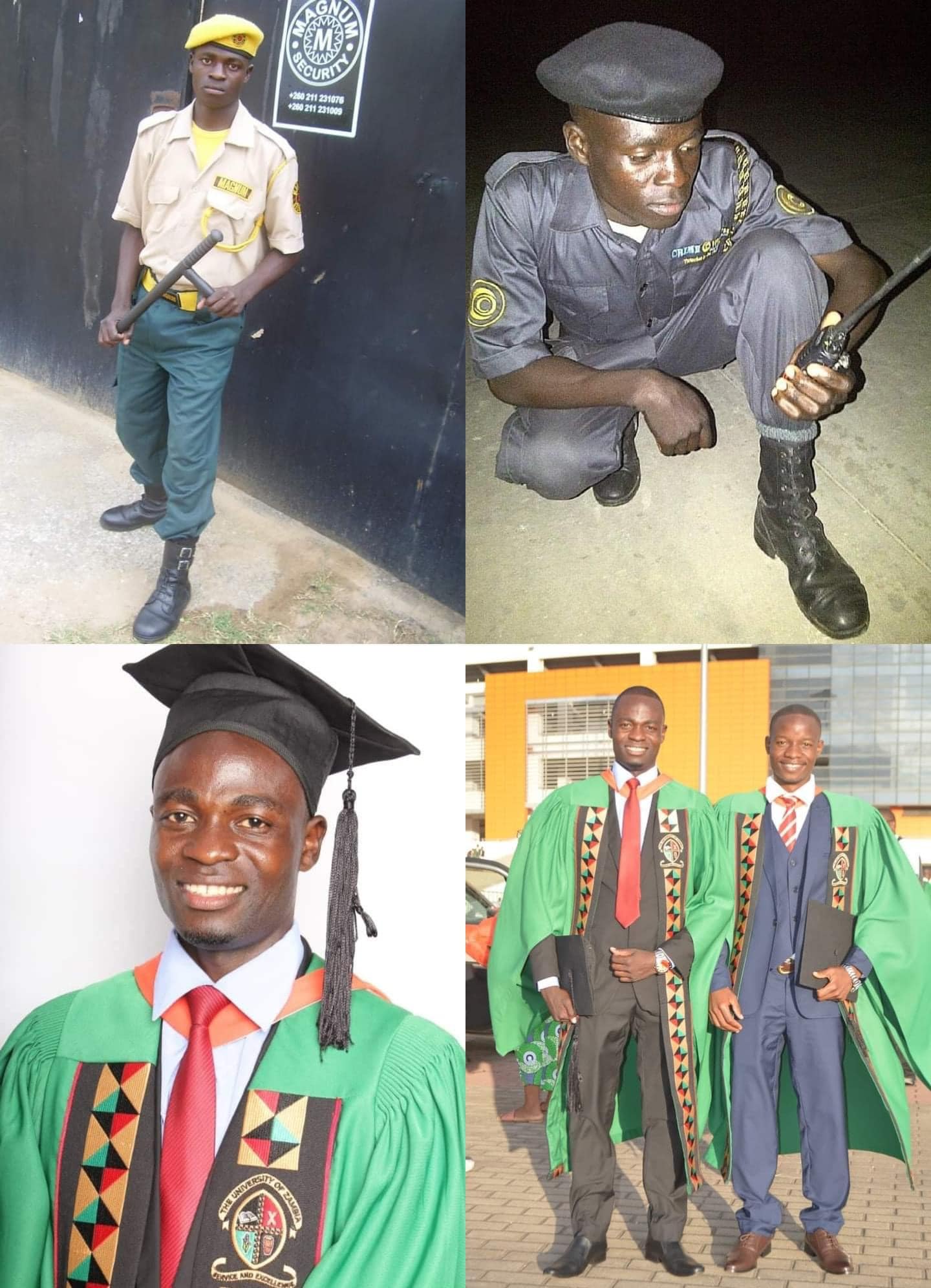

TO THOSE who know Joseph Mambwe, it came as little surprise when they saw this former security guard graduate with a degree from the country’s highest learning institution last month. Mambwe is alien to getting things on the proverbial silver plate and it is not out of choice, rather, life as he knows it never just gave him that luxury. He has, however, encountered ‘miracles’ along the way.

Born in George township, one of Lusaka’s impoverished townships, the odds were heavily stuck against Mambwe from the very beginning. His story traces its plot to 2003 following the demise of his father when a then nine-year-old Mambwe was forced to relocate to Serenje with his mother.

However, their Serenje stay only lasted four years, after which they returned to Lusaka following some family disputes between his mother and some members of her family. “After dad died, we went to Serenje but only stayed there for about four years, following some issues, you know, [between] mum and her family,” he recalls in an interview.

Mambwe’s four year-spell in Serenje disturbed his schooling.

Upon his return to Lusaka, he failed to enroll back into school owing to a lack of resources. However, he got a lucky break when one of his sisters-in-law from his polygamous brother managed to have him enrolled at a community school in Grade Four.

Mambwe’s stay at the sister in-law’s place was short as his mother demanded he joins her at their home in Kanyama even though she was not in a position to fund his school.

Determined to push his education, he resorted to street vending in the central business district selling boiled eggs to members of the public.

“After my sister-in-law paid the initial school fee, mum got me the following year, but she did not have money to keep me in school, so I started selling boiled eggs,” he recalls. His egg business did not last long following a directive by Government to the Lusaka City Council (LCC) to round up all young vendors in town.

“There was a directive from the council that young boys should not be selling in town, so we had to stop that eggs business and started picking scrap metal,” he says.

With his mother working as a maid and not earning enough to sustain the entire family, it was left to Mambwe to fend for his school needs.

“I was paying K35 per month as school fees at the community school I attended, so when we sold the scrap metal I would reserve some money for school while getting some groceries for home.”

Through his scrap metal scavenging, he managed to raise enough money to see him through to Grade Seven, but there was a challenge paying his examination fees.

At Grade Seven, he was the third-highest performing pupil at his school proceeding to Grade Eight, having bagged 768 marks.

In 2010 Mambwe’s educational journey suffered another setback as a lack of finances knocked him out of the Grade Nine examinations.

A people’s person, Mambwe’s announcement to his classmates that he would be stopping school moved his friends to collect donations in an attempt to clear his arrears, but they did not raise enough.

With no hope of a Samaritan coming to his aid, Mambwe started working as a child labourer at a Chinese construction company in Lusaka.

“I was determined to finish school, so I had to look for money. I went to a Chinese company as an under-age to work at the same construction company.

I worked at the Chinese company for a year before going to Kabwe to obtain my NRC (national registration card),” he recalls.

He returned to school in 2012 with the help of his mentor and New Apostolic Church priest Charles Shakantu and went on to pass his Grade Nine exams, scoring 399 marks. “From there, the motivation to continue pushing on was even bigger.

Mum also realised that my future was in school, unlike way back when she never cared,” he said.

Along the way, he received help from his older friend Matomola Mwiya, who worked at one of the community schools in Lusaka, before finishing his education at Mwembeshi Secondary School in 2015.

In Grade 12, Mambwe scored 13 points. Never one to sit at home, he joined a security firm, going on to work for two firms in a period of three years as he waited to be accepted into university.

“I requested that I work in night shifts so that during the day I could be pushing for sponsorship and other things concerning my university school,” he recalls.

Mambwe was picked to study the sociology of education and history at the University of Zambia (UNZA) main campus in Lusaka where he was also awarded government sponsorship.

He was, however, on the verge of missing out on government sponsorship as he did not have his father’s death records to ascertain his eligibility for the bursary as a vulnerable student.

Mambwe’s determination saw him camp at the Lusaka City Council (LCC) offices conducting a manual search for his late father’s record.

“My mother never kept records, she even forgot the year dad died. I started estimating. I went to the record books between 1998 and 2002.

“I managed to find my father’s record at around 14:00hrs. I was interviewed and then awarded the bursary at 75 percent. That is how I stopped working as a security guard,” he says.

Mambwe had to summon his entrepreneurial skills to meet the remaining 25 percent of his school fees as it was not part of his bursary. At UNZA, the industrious Mambwe did side jobs like graphic designing, acting, selling groceries and working on projects to translate books into vernacular to meet his needs.

“I started recording radio dramas. It was about K250 per page and I could make about K7,000 and paid my fees. I got myself a photocopying machine for business, so those monies sustained me,” he says.

Last month, he earned his degree. Other than his determination, Mambwe attributes his story to divine intervention.

“What I can say is that there is hope for everything. I tell people that I stopped school at different stages but that intrinsic motivation kept me pushing,” he says

Source:Zambiareports