The past decade has seen great advances in child survival, but while toddlers and small children are benefiting, the death rate for new-born babies remains stubbornly high. Now a new report suggests that paying more attention to their mothers’ health, and focusing on certain damaging but treatable diseases, could be one key to tackling neonatal mortality.

The traditional childhood killers – measles, pneumonia and diarrhoea – are all down; even where malaria is still rife, treated bednets are saving children’s lives. But as deaths from other causes drop, mortality in the first month of life looms ever larger.

Statistics published recently by researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore show that, worldwide, around 40 percent of children who die below the age of five die in the first month of life, and that rises to 50 percent or more in regions like Europe and South East Asia where other causes of childhood death have been reduced.

Many of these babies were born too soon, or born too small; others were born with infections contracted from their mothers. In all these cases it is the mother’s health during pregnancy which is the key to the babies’ survival, and now the American Medical Association has published astudy of the incidence in pregnant women of health problems which are known to affect their unborn babies, and which can all be treated.

The researchers looked at 171 studies from Sub-Saharan Africa over a 20-year period, which showed whether women attending ante-natal clinics were infected with malaria, or with a range of sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections – syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia and bacterial and parasitic infections of the vagina. If left untreated, these can lead to miscarriages, stillbirths, premature births and low birth-weight babies.

Malaria affects placenta

Matthew Chico, a research fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who led the team, stresses the far-reaching effects of these problems. In malaria, for instance, the placenta does not function properly. “What you end up with,” he told IRIN, “is a low birth-weight baby, and low birth weight is the single most common factor in neonatal mortality. And it leads to lifelong consequences. Low birth-weight babies underperform at school and end up earning less, and curiously they even end up with more cardiovascular problems later in life.

“There are multiple consequences. Girls are at greater risk, for instance, of having low birth-weight babies themselves and so it continues into the next generation. We have to break the cycle.”

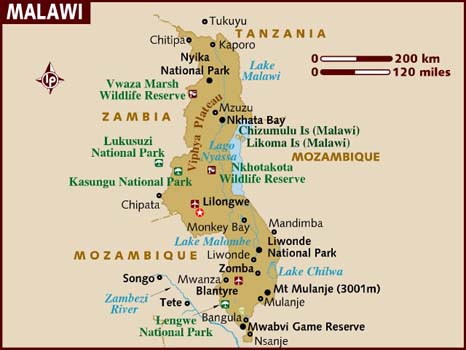

Chico and his colleagues divided the continent into two regions – East and Southern Africa, and West and Central Africa, because of the way the higher incidence of HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa might affect the results. They also excluded South Africa, because malaria was a major part of the study, and malaria there has been reduced to the point where it is no longer an issue.

What they found was alarming. The incidence of syphilis and gonorrhoea was relatively low, under 5 percent, and the most recent figures show them on the decline. But in East and Southern Africa more than half the women attending antenatal clinics tested positive for bacterial vaginal infection and more than a quarter had the parasitic infection, trichomonas.

These figures were a little lower in West and Central Africa, but those areas had a higher rate of malaria infection, around 40 percent, although this had reduced a little in more recent studies, an indication perhaps that the promotion of bednets for pregnant women has had an effect.

The averages conceal considerable variations from place to place, with one set of figures from Blantyre, Malawi, showing more than 85 percent of women had a bacterial vaginal infection and another, from Ngali in Cameroon, reporting that almost 95 percent of women there were infected with malaria.

So what can be done? Effective treatment could make a major dent in neonatal mortality. “It’s been established that universal coverage with preventive treatment for malaria would reduce neonatal mortality by a third,” says Chico. “So add to that an STI [sexually transmitted infection] and RTI [reproductive tract infection] component and the reduction could certainly be more than that.”

The good news

The good news is that all these conditions are treatable. It is just a question of finding the best way to reach these women, many of whom will have no symptoms and be unaware they are infected. The current treatment regime is to give all pregnant women preventive treatment for malaria using Fansidar (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine). But growing resistance to the drug means this is less effective than it used to be.

One possibility is to do a blood test for malaria at each antenatal visit, and only give treatment if the test is positive. “The screen and treat approach minimizes drug use,” Chico told IRIN, “and that would minimize drug resistance. But the test doesn’t show if the placenta is infected, which is what affects the unborn baby, and this approach doesn’t give protection against sexually transmitted infections.

“Or else you could use a preventive combination therapy with an antimalarial plus azithromycin, which is primarily an antibiotic and will act against the other infections, but also has some antimalarial properties. Many doctors don’t like to give a pregnant a woman any drug unless they are sure she needs it, but in this case the alternative is much more grave.

“What we need now are studies to compare the alternative treatments in similar populations. Only then will we know what path to follow.”