Malawi is facing unrest amidst rising prices and falling living standards. Is the hope that was once invested in President Banda running out?

The Malawian government finally gave in to civil servants’ demands for wage increases last week, bringing to a halt rising nationwide strikes. Thousands of government workers across nearly all government departments had been protesting, calling for wage increases to counter the rising costs of living.

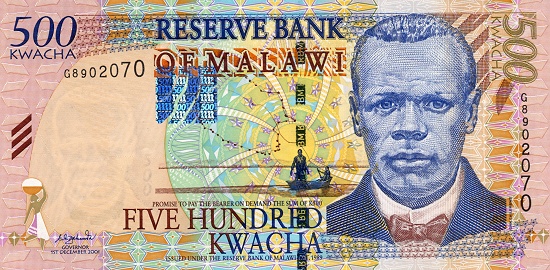

The civil servants claimed that the 49% devaluation of the kwacha last May undermined the value of their salaries and demanded a 65% wage increase. Initially the government insisted such a raise was impossible given the state budget. But as the strikes escalated and expanded, with hundreds of pupils joining the march on Thursday in solidarity with their teachers, the government agreed to a 61% pay hike for the lowest paid civil servants.

Malawi devalued?

When Joyce Banda became president of Malawi in April of last year following the death of Bingu wa Mutharika, she quickly went about reversing many of her predecessor’s economic policies. By the time of his death, Mutharika had largely fallen out with the donor community and was refusing to accept conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Donors, including the UK and US, had frozen their assistance, worth a total of $1 billion, to the country. And the absence of aid inflow, which once contributed 40% to its annual budget, contributed to fuel shortages and a sharp decline in foreign trade.

Banda needed to turn this situation around and wanted to reassure Malawi’s erstwhile donors. One of the most significant ways in which she did this was to devalue to kwacha, something Mutharika had vehemently refused to do. Mutharika had claimed it would have devastating effects on the populace and had pointed to the 10% devaluation he made upon instruction from the IMF in 2011 which resulted in a sharp increase in the prices of goods and services.

On taking office, however, Banda saw these short-term dangers as necessary. Banda devalued the kwacha by almost 50%, well above the 30% suggested by the IMF mission which had visited the country just before Mutharika’s death, claiming the action was the only route to get the economy back on track.

The cost of basic goods rose dramatically and commentators warned of dire consequences unless the government devised measures to cushion the impact. Such predictions seem to have been vindicated, with the rising prices and falling living standards her predecessor had warned of becoming starkly apparent to ordinary Malawians. A recent Integrated Household survey found that 52.2% of the country’s population is now in poverty, surviving on less than a dollar a day. Meanwhile, the number in the most extreme poverty, surviving on less than 10 cents a day, has increased from 22% to 25%.

Finding funding

In January, some groups such as the consumer lobby organisation, the Consumers Association of Malawi, organised protests in the country’s major cities and towns calling for the government to reverse its economic policies. Following this, government workers went on a two-week strike which eventually forced the government to concede to the 61% pay rise.

While this wage increase has been welcomed by civil servants and others, many are concerned at the news, especially after Ken Lipenga, Malawi’s Minister of Finance, had earlier warned that meeting such a demand would triple the public servants wage bill from around $263 million to $786 million – a situation he warned could lead to the collapse of government.

“If we go down that route then we should forget recovering from the difficulties that we are trying to recover from now”, he said, “[we would be] returning not only to the way we were before the reform, but a worse situation where the economy would simply collapse.”

Mark Katsonga, president of the opposition party People’s Progressive Movement (PPM), told reporters in Blantyre that although it’s good news that the civil servants got what they were bargaining for, more government clarity is needed on the precise source of these wage increases.

“The Minister of Finance, who knows our coffers, said if we give in to those demands government is going to collapse”, explained Katsonga. “But now we are hearing that negotiations reached a point of compromise for a 61% salary increase. Now we are failing to reconcile the two. Are we driving the government into bankruptcy or what are we doing?”

The answer was arguably given by government spokesperson Moses Kunkuyu, who claimed money for the civil servants’ wage hike had been sourced through cuts in ministerial budgets, State House spending, and other areas. He also said the government had already started responding to some of the demands in the previous January petition, citing the selling of the presidential jet, reduction of the presidential convoy, and selling off of some ministerial Mercedes-Benzes.

But nevertheless it seems unlikely the state finances can be rescued through these actions alone, especially as many other areas are suffering from lack of resources. The country’s public hospitals, for example, are currently experiencing acute drug shortages, a situation which health authorities are blaming on the effect the floatation of the kwacha has had on the drugs procurement budget.

Health Minister Catherine Gotani Hara told reporters that Central Medical Stores (Malawi’s government-controlled drugs stores) is running 95% short of drugs. This forced medical authorities to write an open letter to president Banda, asking her to intervene to stop public hospitals from becoming “waiting rooms for death”.

Accountable to whom?

The scale of the recent protests should be a wakeup call to President Banda’s administration. If the situation is left uncorrected, it could cost her dearly in the 2014 elections.

“Although the impact of devaluation was expected, the problem is that many people in the country were expecting the best from the current administration and are not ready to take any excuses”, political scientist Mustapha Hussein told Think Africa Press.

However, the IMF is more hopeful. The team headed by Tsidi Tsikata which recently visited Malawi to assess the progress of economic reforms, described Banda’s economic policies as satisfactory. An IMF press release issued at the end of the mission cited improved price incentives for tobacco production and good rains this season as reasons for optimism. Looking to the longer term, the IMF team urged “a tight monetary policy stance until inflation pressures recede”. Banda’s government was also encouraged to “continue implementing structural reforms designed to remove regulatory hurdles and improve the investment climate”, thus safeguarding financial stability and promoting growth.

However, the IMF mission did ask Banda’s administration to improve in its response to the “growing public outcry over falling living standards and perceived wasteful spending and fraudulent activities in the government sector”.

And this is surely the crux of the issue. No matter how well-intentioned Banda’s economic reforms are, if she loses the support of the people before they start yielding positive results, there is a real chance of administrative collapse in the country. Should this come to pass, Banda’s political failure would be a devastating disappointment for a population which once invested so much hope in her.