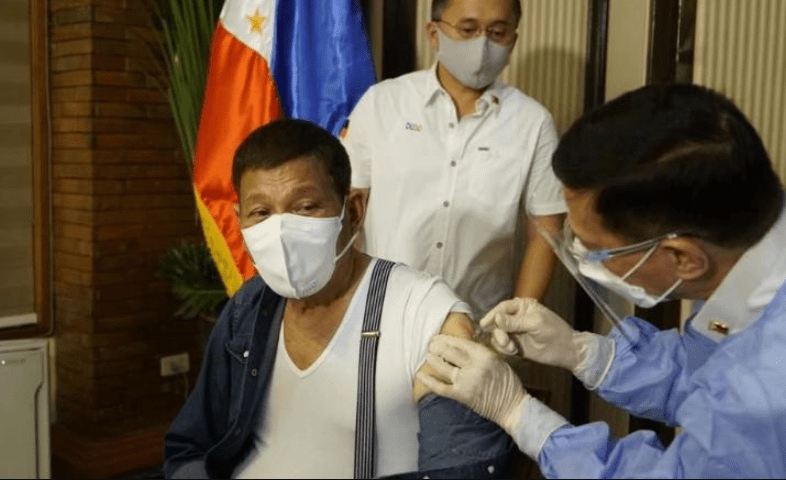

When Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte live-streamed himself receiving a first dose of the Chinese-made Sinopharm vaccine on Monday, it was supposed to encourage reluctant Filipinos to follow his lead and protect themselves against Covid-19.

Instead, it drew a firestorm of criticism against Duterte — for choosing a vaccine not yet approved by the country’s regulators.

Amid the backlash, Duterte on Wednesday asked China to take back the 1,000 doses of the Sinopharm vaccine it had donated to the Philippines and apologized to the public for receiving the unapproved shot.

Duterte said he had told the Chinese ambassador to stop sending Sinopharm. “Just give us Sinovac, which is being used by everyone,” he said, according to local media, referring to another Chinese vaccine that was granted emergency use in the Philippines in February.

It was the second piece of awkward diplomacy between the Philippines and its large neighbor in a week, after Foreign Minister Teddy Locsin had to apologize for an expletive-laced tweet about Beijing’s activities in the South China Sea.

Duterte’s about-face on the Sinopharm shots highlights the regulatory roadblock faced by Chinese vaccines in the absence of an emergency use approval from the World Health Organization (WHO), even though the shots have been approved for use in dozens of countries.

When Sinopharm applied for emergency use with the Philippine Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in early March, the agency’s director said that, as with the case of Sinovac, it would take longer to decide on Sinopharm’s application because it hadn’t been approved by a “stringent regulatory authority,” such as WHO.

But that could soon change. WHO said at a press briefing Monday that it expected to finalize decisions on the emergency use approval for both of the submitted Sinopharm and Sinovac’s vaccines “by the end of this week.”

An endorsement from WHO may finally boost confidence in the Chinese vaccines, which have long faced concerns about efficacy rates and a lack of transparency regarding clinical trial data.

The Sinopharm and Sinovac shots are both inactivated vaccines, which are lower in efficacy than the mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. And unlike their Western counterparts, the two Chinese companies have not released full data of their last stage clinical trials conducted around the globe, drawing criticism from scientists and health experts.

According to Sinopharm and Sinovac, their vaccines received different efficacy results in trials conducted in different countries, but they all exceeded WHO’s 50% efficacy threshold for emergency use approval.

Their approval could be timely for COVAX, the global initiative backed by WHO to ensure equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines. In recent weeks, it has faced a severe shortage of supplies from India, which halted export of the AstraZeneca vaccine amid its Covid-19 crisis.

Because COVAX can only distribute vaccines approved by WHO, as of now, Chinese vaccines have not been included in its portfolio. It instead has to rely on Pfizer-BioNTech, AstraZeneca, Covishield from the Serum Institute of India, Johnson & Johnson, and Moderna, which are all in high demand.

Instead, China has been making its own donations of vaccines via bilateral agreements with individual countries, including the Philippines — an effort experts say is guided more by China’s strategic interests than the needs of the most-vulnerable countries.

The approval from WHO will no doubt boost Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy. But more importantly, it should help provide better protection against Covid-19 to countries in greatest need.