The longest-serving death row inmate in the U.S. was resentenced to life in prison last Wednesday after prosecutors in Texas concluded the 71-year-old man is ineligible for execution and incompetent for retrial due to his long history of mental illness.

Raymond Riles has spent more than 45 years on death row for fatally shooting John Thomas Henry in 1974 at a Houston car lot following a disagreement over a vehicle. He is the country’s longest-serving death row prisoner, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Riles was resentenced after the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in April that his “death sentence can no longer stand” because jurors did not properly consider his history of mental illness.

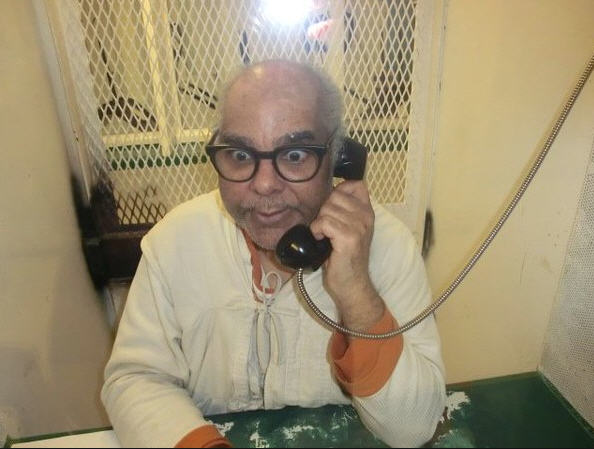

Riles attended his resentencing by Zoom from the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, which houses the state’s death row inmates. He said very little during the court hearing.

Riles’ attorneys asked that he appears via Zoom because they were concerned his various health issues, including severe mental illness, heart disease, and ongoing recovery from prostate cancer, make him susceptible to contracting COVID-19.

Several members of Henry’s family took part in the virtual court hearing but did not make any statement before state District Judge Ana Martinez resentenced Riles to life in prison.

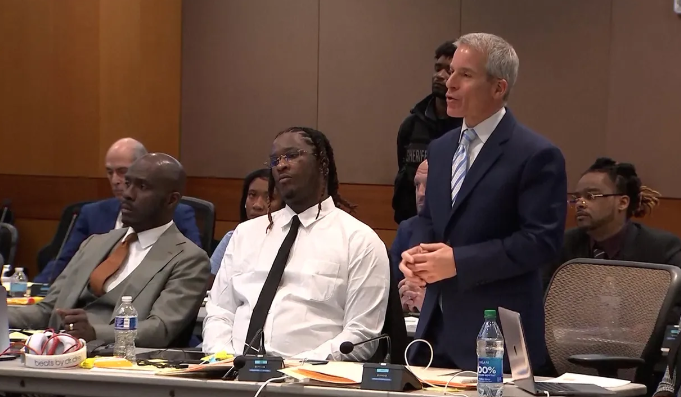

“We express our condolences to the family of Mr. Henry (who) we know have suffered an unimaginable loss. We are profoundly sorry for that,” said Jim Marcus, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law and one of Riles’ attorneys.

In a statement, Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg said Riles is incompetent and “therefore can’t be executed.”

“We will never forget John Henry, who was murdered so many years ago by Riles, and we believe justice would best be served by Riles spending the remainder of his life in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice,” Ogg said.

During his time on death row, Riles has been treated with heavy antipsychotic medications but was never deemed mentally competent to be executed, according to prosecutors and his attorneys.

He had been scheduled for execution in 1986 but got a stay due to competency issues.

While Riles spent more than 45 years on death row in Texas, prisoners in the U.S. typically spend more than a decade awaiting execution, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Martinez was not able to resentence Riles to life in prison without parole because it was not an option under state law at the time of his conviction.

Riles’ new sentence means he is immediately eligible for parole.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles will automatically conduct a parole review in his case, Marcus said.

The district attorney’s office as well as Henry’s family have indicated they will fight any efforts to have Riles released on parole.

“Mr. Riles is in very poor health but, if the Board of Pardons and Paroles sees fit to grant parole, he has a family with the capacity to care for him,” Marcus said.

A co-defendant in the case, Herbert Washington, was also sentenced to death, but his sentence was overturned, and he later pleaded guilty to two related charges.

He was paroled in 1983.

When Riles was tried, state law did not expect jurors to consider mitigating evidence such as mental illness when deciding whether to choose the death sentence.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1989 that Texas jury instructions were unconstitutional because they didn’t allow appropriate consideration of intellectual disability, mental illness, or other issues as mitigating evidence in the punishment phase of a capital murder trial.

But Riles’ case remained in limbo because lower courts failed to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision until at least 2007, according to his attorneys.

That then gave Riles a realistic chance to prevail on this legal issue, but it wasn’t until recently that he had contact with attorneys who were willing to assist him, his lawyers said.

While prosecutors argued at Riles’ trial that he was not mentally ill, several psychiatrists and psychologists testified for the defense that he was psychotic and suffered from schizophrenia.

Riles’ brother testified that his “mind is not normal like other people. He is not thinking like other people.”

While the Supreme Court has prohibited the death penalty for individuals who are intellectually disabled, it has not barred such punishment for those with serious mental illness, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

In 2019, the Texas Legislature considered a bill that would have prohibited the death penalty for someone with severe mental illness. The legislation did not pass.