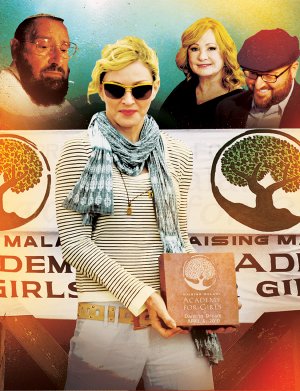

One year ago, Madonna squatted in the rust-colored dirt of a sprawling empty lot outside Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the world. With curious villagers and invited photographers crowding around, she laid the ceremonial first brick for a planned $15 million girls’ academy, a noble mission in a nation where only 27 percent of girls attend secondary school. In a blog post on the website of her Raising Malawi foundation, she wrote that the brick, inscribed with the words “Dare to Dream,” was “not just the bedrock to a school—it is a foundation for our shared future.”

Last week it was announced that the future would not be built. Despite the fundraising success of Raising Malawi, which collected a reported $18 million in donations and spent $3.8 million on the planned academy, the girls’ school has been abandoned and the Raising Malawi foundation has imploded.

From its inception in 2006, the pop superstar has been the face of Raising Malawi, generating headlines around the world by adopting two Malawian children, writing and producing a documentary about Malawian orphans, and hosting high-profile fundraisers, including a star-studded event in 2008 co-hosted by Gucci in a 42,000-square-foot transparent tent on the north lawn of United Nations headquarters. “I want credibility as a philanthropic organization,” Madonna told the $2,500-a-plate crowd.

To understand what went wrong, one has to look at Madonna’s partner in the foundation, a mysterious and controversial organization called the Kabbalah Centre International, which is now a focus of federal investigators. The center is a Jewish mystical organization that follows a set of esoteric teachings called Kabbalah, which adherents believe explains the relationship between humans and their creator and our true purpose in the universe. Madonna has said that she turned to Kabbalah in 1996 when she was pregnant, exhausted from Evita, and looking for an anchor. Since then she has reportedly donated at least $18 million of her personal fortune to the Kabbalah Centre.

The center was founded by Philip Berg, a Brooklyn-born New York Life insurance agent whose first wife happened to be the niece of a famous Kabbalist, Rabbi Yehuda Brandwein. Berg sired eight children with her, but soon after the rabbi’s death in 1969 he left his wife for his former secretary, Karen. Two years later they launched their own idiosyncratic brand of Kabbalism, popularizing what had until then been teachings reserved for advanced Talmudic scholars. The Bergs eventually expanded to 77 centers and study groups around the world.

The Kabbalah Centre’s impressive growth has been paralleled by the volume of its detractors, some of whom have labeled it “Jewish Scientology.” Disaffected followers have accused Berg and his family of treating congregants like personal servants, housing them four to a bedroom, paying them a $35-a-month stipend, and advising them to apply for food stamps. One prominent critic, Rabbi Immanuel Schochet, has said, “They are distorting Kabbalah .?.?. taking some of our sacred books and reducing it to mumbo-jumbo, all kinds of hocus-pocus.”

Berg, who is now 81 and referred to by insiders as “the Rav” (an honorific meaning teacher), is still very much the patriarch of the Kabbalah Centre, despite a stroke in 2004. But day-to-day operations are controlled by his wife, Karen, 68, and their two sons, Michael, 37, and Yehuda, 38, all of whom share the title of codirector.