Among the numerous horror stories involving the mismanagement of foreign aid funds, most involve some corrupt NGO or government official siphoning off millions of dollars intended for the world’s poorest. The problem, foreign aid critics feel, is not the motives behind assistance. Few would argue for leaving the poor to fend for themselves. Rather, detractors focus on how we use aid funds—how much donors give, who donors give money to, and the types of projects donors focus on. Lately, buzz words such as “transparency” and “accountability” have been thrown around in the development world as remedies to the problems of misspent aid funds.

Among the numerous horror stories involving the mismanagement of foreign aid funds, most involve some corrupt NGO or government official siphoning off millions of dollars intended for the world’s poorest. The problem, foreign aid critics feel, is not the motives behind assistance. Few would argue for leaving the poor to fend for themselves. Rather, detractors focus on how we use aid funds—how much donors give, who donors give money to, and the types of projects donors focus on. Lately, buzz words such as “transparency” and “accountability” have been thrown around in the development world as remedies to the problems of misspent aid funds.

Both critics and supporters acknowledge the lack of transparency in foreign aid as an obstacle to efficient development assistance. Obtaining specific information on aid projects can be challenging. Lately, the “Open Data” movement has been making a big push to have donors publish project details online for public consumption. A year ago, the World Bank took a much heralded step in releasing to the public thousands of documents from project information sheets to environmental assessments, to the public. Other government aid agencies such as DFID (Department for International Development, the UK’s development agency) and USAID (the US counterpart) are following suit in publishing more information on their activities online.

However, increased availability does not always lead to increased accessibility. Just because the information is available doesn’t make it easily digestible. Many of the World Bank documents are not exactly light reading; most are dense, acronym- and jargon-filled, 50 page-plus documents, which, admittedly, is necessary for complicated projects that require specialists to implement. However, that doesn’t make it any easier for your average citizen or NGO to quickly read through and capture essential information. Your average citizen probably doesn’t care about the specifics of drilling boreholes in Malawi but rather is more interested in the type, location, and effectiveness of the projects.

Initiatives such as IATI (International Aid Transparency Initiative) are a necessary beginning, but simply making documents available is not enough. Much of the data still needs processing. For example, World Bank aid documents list implementing partners, or the organizations that actually use aid funds to build roads, train officials, and so on. While the data is there in a very raw form, compiling aggregate statistics or even finding the implementing partners of a specific project requires a laborious search through World Bank documents. The result is a lack of research, information, and ultimately transparency.

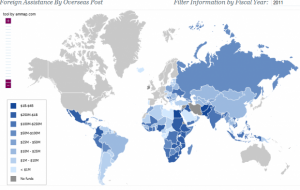

Fortunately, the World Bank and other NGOs such as Development Gateway (with whom—disclaimer—I am interning this summer) have taken the time to sift through the data and present it in nice maps, charts, and searchable databases. AidData has gone through hundreds of thousands of aid projects and coded them by sector, greatly facilitating research. Mapping for Results, an initiative from the World Bank, has developed maps that show the location of World Bank aid projects around the world. Overlays that show indicators such as poverty allow the user to determine whether donors are targeting the poorest sectors. USAID has recently rolled out its foreign assistance dashboard that shows data on aid by country and by sector.

The graphs and maps are not only pleasant eye candy; they also make information gathering user-friendly. Current World Bank and USAID initiatives make international development truly transparent by making the data accessible, not just available. Admittedly, complications can arise from processing data. Filtering and compressing data into pretty charts can introduce biases into the information depending on who is creating the charts. Despite these potential problems, more efforts need to be supported to make data on aid open to the public and to researchers. For all the actors in the aid process to truly be empowered, data must not only be available but also accessible.

http://praemon.org

No comments! Be the first commenter?