Who said partisan politics does not have a training school? Jomo Kenyatta’s life provides solid training ground for those who aspire to become presidents. The starting point must always be grassroots leadership. Instead of starting from the grassroots, leaders in some democracies start by showing off their academic qualifications or memberships to social clubs as requisites for the job. This is where everything starts going wrong, voters’ expectations are not met and voter apathy sets in. A good political leader for an African democracy must be one who is well steeped in the life of the poor even if it means growing up in the village, sleeping without a mattress, lead a grassroots youth movement and, at times, sleeping without food.

When leaders understand and appreciate what the ordinary folks go through, they are better able to provide relevant leadership and respond accordingly to people’s needs.

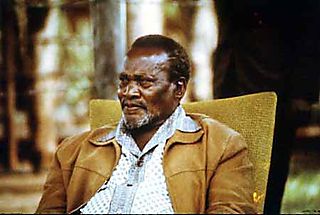

Jomo Kenyatta was first and foremost a villager. He was the son of Kikuyu parents whose real name was Kamau wa Ngeni. Jomo Kenyatta was a name he gave himself in London when he felt qualified as a political agitator to fight white settler farmers in his Kikuyu land. The name had two different meanings, namely, Jomo burning spear and Kenyatta, a coloured beaded belt which he often used as a young man when he worked as a junior civil servant in the Water Department.

Like most contemporary leaders of the time, Jomo Kenyatta did not know his date of birth. When asked by journalists his age, he often replied; “I do not know when I was born, what date, what month and what year.” However, historians estimate the 20th of October, 1893 as his official birthday at his Ichiweri Village in the Kikuyu land of Kenya.

He had life similarities to his best friend, founding President of the Republic of Malawi, late Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda. Jomo Kenyatta was a protégé of the Church of Scotland. The same was true of Dr Banda. At one time, Jomo worked as kitchen servant where his employer nicknamed him “John Chinaman” because of the appearance of his eyes resembling the Chinese.

At his baptism in 1914, a Scottish missionary christened him Johnston. Kamau wa Ngeni had become Johnston Ngeni. The same story was true of his close friend Kamuzu Banda who also changed his native name to John Hastings after a Scottish missionary. It is probably these similarities that influenced the two founding presidents to forge strong personal friendship whilst in the United Kingdom as the saying goes; “birds of the same feathers flock together”

After working in the kitchen Johnson Ngeni joined the civil service as court interpreter in the Supreme Court. He worked for the court for a short time and later joined the Water Department as plumber, riding a bicycle from 1921 to 1926. It was while working in the Water Department that Johnston Ngeni became well known in Nairobi. He habitually wore a beaded red, black and green belt popularly known as “mucibi wa kinyatta”. This earned him the nickname “Kenyatta” which he later accepted as a political surname in London to leverage on his previous popularity in the Water Department.

It was as a young worker in the Water Department that Johnston Ngeni started to become popular among the Kikuyu tribe. It was from this background that he joined the Young Kikuyu Association. The association was established in 1920 to agitate for transfer of land from white settler farmers to indigenous blacks in the Kikuyu land. From a tribal association the group gained political posture and became a formidable political force that fought for the return of native land from the settlers. His previous experience in the Supreme Court gave him comparative advantage among his fellow Kikuyu citizens to elect him Secretary General.

The fight for land became very strong and Kenyatta its spearhead. The name of the Young Kikuyu Association was changed to Kikuyu Central Association. As leader of the association, Johnston Ngeni was a fiery orator who imbued the association with a pan-Kikuyu political consciousness. The white settlers recognized these capabilities and described Johnston Ngeni as a dangerous man. He established a monthly newsletter called Mwigwithania, meaning the “Reconciler” and he was its first editor. The paper covered a number of issues including land productivity, cleanliness, education and religion.

In 1929, Johnston Ngeni was sent by his association to present their grievances in London to the British Secretary of State. His mission was not successful as only the Under Secretary of State received the list of grievances. Nevertheless, while in London he received moral support from critics who were against white settlement in Kenya and also received financial support from the League Against Imperialism in Africa. Undaunted with the failure to meet the Secretary of State, Johnston Ngeni travelled to Moscow and Berlin in Germany to get exposed to international politics. He later returned to England to try a second time to meet the Secretary of State. Again, he failed. He returned to Kenya more experienced in politics.

It was while in London that he voluntary named himself Jomo Kenyatta. Jomo Kenyatta’s long journey into politics had started. It was not academic education first but personal sacrifice and a great passion for social justice. Fertile land in his country was under the control of white settler farmers. His people needed the land back.

Consequently Jomo Kenyatta started his political life from a grassroots youth movement and rose to Secretary General, then editor and later emissary. He moved through the political ladder from grassroots to the presidency.

Looking at some African leaders, one is left with the impression that they rise to the Presidency through the back door. They have no commitment to the people’s welfare. They behave arrogantly and look down upon the electorate.

Kenyatta’s life should serve a great lesson to all of us in Malawi as we prepare for the 2014 General Elections.

We should not be deceived by academic labels or age. It is the heart, commitment to people’s welfare and practical experience that matter. It is obvious that electing a president who has no experience from the grassroots is the beginning of problems. Grassroots leadership is the political school and not university.

This is the time tested political school for effective Presidents.

BREAKING NEWS

- Kenyan Model ‘Lydia Nditi’ Goes Viral After Her Self-Treatment Video Leaks

- ‘Please address the Nation or step down’-Chimbanga tells Chakwera amid fuel crisis

- Meet the tribe where bride’s aunt tests groom’s bedroom skills (READ)

- MLW and QECH Hold “Big Walk” to Raise Awareness on Antimicrobial Resistance

- Woman banned from stadium after she str!pped completely and ran across field during game (Watch video)

- Minister Kunkuyu stoned in Ndirande, police fires teargas

- Inkosi ya Maseko Gomani V welcomes second child

- ICC Sentences Former Islamic Police Chief in Timbuktu to 10 Years for War Crimes

- Leslie to Perform at“Ulendo Leslie Unplugged Acoustic Story” at Amaryllis Hotel

- ACB Arrests Six Individuals Over Fraudulent Health Worker Recruitment in Phalombe

No comments! Be the first commenter?