By Andrew Evans of National Geographic Traveler .

By Andrew Evans of National Geographic Traveler .

Yesterday, the President of Malawi, Bingu wa Mutharika died from a heart attack.

I first heard the rumors about the president’s failing health outside a sugar ration line in central Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi, where I was told that the he had collapsed and was now in a coma. I immediately tweeted what I had heard (#unconfirmed) and then began to follow leads that popped up on Twitter.

The news was very quiet—relayed in uncertain voices from one person to another, and by text message on cell phones. Lilongwe is not a big city and people know one another. When the city’s main hospital is sealed off and surrounded by a legion of police, there are no secrets. The news is whispered across town fairly quickly.

Over lunch, I gathered more information on the streets and market of Lilongwe. By late afternoon, I heard that the president’s security detail had been sent home from the hospital. That’s when people started saying that he was dead. I assumed the chatter meant that the president was either gone from the country, or in fact dead. At this point, there seemed to be a little more buzz in the streets, though there was some confusion since the government had announced that the president was in “critical condition” and that he had been airlifted to South Africa for intensive care.

That’s when I went to the hospital. I merely asked my driver to swing by Kamuzu Central Hospital so that I could see for myself what was going on. When we arrived there was only one police jeep, with five police in it, who were not even sitting by the entrance. They seemed rather oblivious and we drove into the hospital compound without any problems.

Nothing seemed out of the ordinary to me at the hospital—there were women dressed in chitenjes walking from different wings. I saw a few nurses outside. And I saw an ambulance parked in a paved courtyard, with its back doors wide open.

As we pulled the car around, I took pictures from the window, though I recorded nothing of consequence. The hospital was quiet and rather empty looking.

That’s when we were spotted and approached by three men in civilian clothing who jogged up to the car as we were reversing. They demanded that we stop, and surrounded the car from the front, back and middle.

“What are you doing here?” They pointed at me. “You are taking pictures!”

The largest of the three men revealed that they were “police detectives” and that they were going to delete my photos from my camera.

I told them I was allowed to take pictures and that we were leaving just now, but they refused and made a grab for the keys of the car. Luckily, my driver pulled them back and would not hand over the keys. I told them that I was a journalist and that I had a press pass.

Then one of the men reached for my camera through the window of the car, but I pulled it away. He demanded my iPhone and also tried to grab it, but I refused to hand it over. I also refused to show them my passport, telling them they did not have the authority to see it.

The only thing I handed over was my press pass for Malawi, issued to me by the Secretary of Information earlier that week. After some shouting and arguing, I asked to see their identification, but the small papers they showed me were very unconvincing.

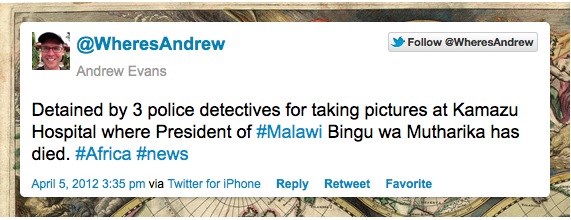

As the police questioned me, I never let go of my phone. Instead, I just kept tweeting everything as it was happening to me. When it became clear to me that the situation had the potential to be serious, I tweeted that I had been detained.

Screen grab by Andrew Evans, National Geographic Traveler

The police harassed me for about 20 minutes, during which time I got out of the car and began threatening to call the US Embassy unless they released me immediately. I looked up the number on my iPhone and began dialing.

At this point, the detectives became less aggressive and more explanatory, asking that I wait while they contact their superiors to decide what to do with me. When I pretended to be calling the embassy anyway, they balked and said, “Our head of state is here at the hospital right now. You cannot be here.”

That’s when I knew they were lying, since it was the opposite story to the official one being broadcast in Malawian news. The president could not be in two places at once.

“I have spent the last week driving half the length of your country. There are police checkpoints everywhere that you must stop for,” I said to them. “If your president is in this hospital, then how is it there is only one police car and that I was able to simply drive to the back parking lot of the hospital?”

The three men looked at me dumbfounded, unable to answer. They kept going back and forth, consulting with other plainclothes agents, saying that they needed to “find out what to do with me.”

“I’m calling the U.S. Embassy now!” I said, and pretended to be on the phone. That is when one of them returned and seethed at me, “Get out of here and go away from here now!”

I happily complied, jumping back in the car and telling the driver to scram before they changed their minds. We drove away from the hospital, and this point, I saw there had been a new roadblock set up for all traffic entering the city (but not leaving).

I asked the driver to swing past State House, the president’s official residence, but I only saw two trucks leave through the main gates.

All night long I followed the moving stream of chatter on Twitter: Malawians, Malawians abroad, Africans and politicos all over the world. The odd mix of rumors and news pointed at the significance of this man’s death. Mutharika was only the third president in this young African country, and the political tangle around him means that the transition of powers to a new government will be tricky.

I received more confirmations throughout the night that indeed, the president was dead. Sources had seen his body.

This morning, the streets of Lilongwe were very quiet. It seemed that the capital was waking up to a strange awareness that everything had changed or was about to change. The confusion of the official news versus the unofficial reality also had people whispering in corners and consulting with one another quietly.

And yet people were happy. Many were already openly jubilant. At my hotel, a few staff had asked their boss if they could kill a goat in celebration. While some of the social media I read seemed sympathetic to the deceased president, most Malawians disliked him. All week long, I have been made aware of the president over and over again—it seems every problem is attributed to his administration: the severe sugar and fuel shortages, the lack of foreign currency reserves, the false exchange rate, the astronomical prices of food, and the ruined relations with Britain and the United States. That he died was no great tragedy in this country, one of the poorest in the world.

I was already set to leave Lilongwe today and head to the airport in the morning. While some of the mainstream media reported that the city is “braced for violence,” I disagreed. Malawians are some of the most tranquil and easygoing people around. If there is to be any kind of massive street protest, it will simply be a giant block party in Lilongwe. I think the humble majority of Malawians are relieved to see this autocrat take his leave.

My final moments in Malawi were slightly Orwellian, as I sat in the airport lounge, observing the reaction of the Malawians around me.

On a table in the airport lounge sat today’s newspaper, the Daily Times (“Malawi’s Premier Daily”) announcing today’s headline, “Bingu’s Illness Creates Anxiety” while at the very same time, the BBC World Service blared President Bingu’s death from television screens, “President Bingu has died of a heart attack.”

The Malawians watched the televisions with utter shock, listening to the new reality of their own country from a foreigner so far away.

I was keen to hear their thoughts, but when it comes to talking politics, I find the people of Malawi to be very reticent and careful. Only after I presented my boarding pass to the agent and was walking out to the runway was I able to ask three airport custodians what they thought.

“What do think about the president dying?” I said.

Two of them stared at me blankly, afraid to answer. But the man in the middle finally showed me a very hesitant African smile with a slim row of all-white teeth, and spoke:

“It is well.”

No comments! Be the first commenter?